04.19.23

RULES OF RESTRAINT: KELLY REICHARDT & CHRISTOPHER BLAUVELT

Over the past 30 years, the films of Kelly Reichardt have become one of the most significant bodies of work in American independent cinema. Known for her naturalistic style and interest in characters living on the margins of society, Reichardt’s movies are synonymous with restraint, minimalism, and a rejection of the extravagances of much of mainstream American cinema.

Central to the style associated with Reichardt’s work is American cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt. Blauvelt and Reichardt have collaborated on Reichardt’s past five feature films: Meek’s Cutoff (2010), Night Moves (2013), Certain Women (2016), First Cow (2019) and Showing Up (2023). While each of these five films have told unique stories with different visual approaches and have faced different creative challenges, Reichardt and Blauvelt have developed a consistent working relationship that has allowed them to create an instantly recognizable style.

In this article, we will examine five of the core “rules” of Reichardt and Blauvelt’s working process, and show how that process impacted each of the five films they have made together.

ART AND REFERENCE FILMS: FIRST COW (2019)

Blauvelt has spoken about Reichardt being a particularly visual writer-director, with a clear set of aesthetic principles built into the script from the outset. The pair often make decisions about visual language before pre-production starts, discussing aspect ratios, lenses, film stocks and processes by starting with the references Reichardt has collected.

Reichardt builds digital folders of visual references for each scene in the film, annotating paintings, photography, sculpture, textiles and film stills alongside excerpts from the script. This serves as a starting point for the technical conversations she and Blauvelt have about how to translate these references into a cogent visual language. The end product is a detailed shot list that is used to align Reichardt and Blauvelt on their intentions for each scene.

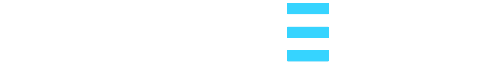

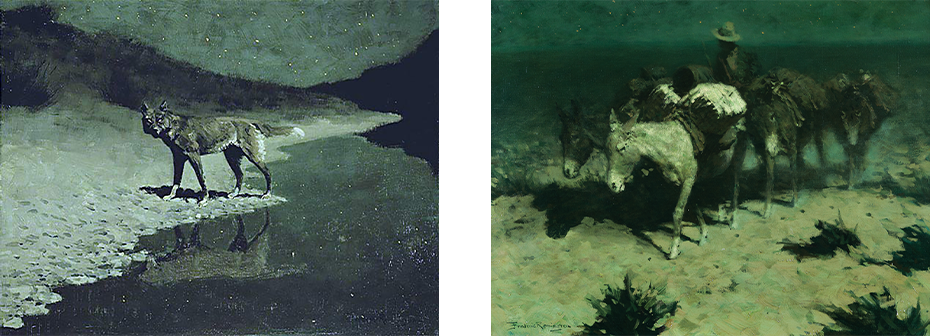

In First Cow, a big component of Reichardt’s aesthetic goals involved seeing landscapes in the background of frames at night, inspired in part by the work of Frederick Remington who painted images of western landscapes at night. And despite these paintings depicting the nighttime, they still had warmer yellow and brown tones alongside the blue and cyan night skies. When Reichardt and Blauvelt discovered that Remington almost always painted his night landscapes during the day, they decided to employ day for night cinematography for First Cow.

Blauvelt studied day for night photography in Yasujiro Ozu’s black and white films and in older color films, but wanted to create a more naturalistic look than he was seeing in the references. After two months of experimenting with camera assistant Jordan Green and DIT Sean Goller, Blauvelt arrived at a day for night look shooting on the ARRI Alexa Mini that he was pleased with. The effect of moonlight was created by the sun going through dappled foliage, or by recreating the dappled look with several small lighting units. Blauvelt, Green and Goller calibrated the camera differently depending on the environment they were shooting in, developing a convincing and naturalistic day-for-night capture methodology along the way.

LOCATION SCOUTING AS RESEARCH: MEEK’S CUTOFF (2010)

Every film that Reichardt and Blauvelt have made together has included extensive location photography, and the pair use location scouting not only as a way to find where they want to film, but also as a way to study how they want to film their movies. It is not uncommon for Reichardt and Blauvelt to begin location scouting over a year in advance of principal photography, using the scouts themselves as a catalyst for discovering new insights about the characters and the visual style of the film.

For Meek’s Cutoff, Reichardt insisted on shooting in the same desert where a wagon train of 200 wagons and 1000 people led by Steven Meek got lost as they deviated from the Oregon Trail. Before pre-production began, Reichardt went to southern Oregon with production designer Dave Doernberg and costume designer Vicki Farrell. She and Blauvelt communicated about the feeling of the landscape and how that would dictate the compositions and camera operation of the film. Stemming from these scouts, Blauvelt chose a shooting approach dominated by low-angled, static shots with balanced compositions that placed the horizon line either low or in the middle of the frame, generating a stillness in long takes that allowed the audience to understand the wagon train’s relationship to time in this environment.

Location scouting also allowed Blauvelt, Doernberg and Farrell to collaborate on the color language of the film, and build a palette for the production design and costume design out of the colors of the earth, the sky and the vegetation that surrounded them in the landscape.

COLLABORATION WITH PRODUCTION & COSTUME DESIGN: CERTAIN WOMEN (2016)

Reichardt and Blauvelt’s collaboration with the production design and costume design departments is an essential component of how they build the aesthetic language of their films. The pair often scout locations alongside the production designer and costume designer months in advance of the shoot, using the same visual references as a guide for the world they want to build and the colors they want to explore through the characters’ costumes.

In Certain Women, Reichardt was interested in the isolation and loneliness created by the landscapes they were filming in. She used the paintings of Milton Avery as the core initial reference, including a different collection of his paintings as study material for each scene of the film. These became the foundation for how she and Blauvelt designed the shot list, but also for how production designer Anthony Gasparro and costume designer April Napier built the clothes and environment of the film.

The landscapes that the team found during location scouts helped Reichardt and Blauvelt decide to shoot the film on 16mm. The pair were initially interested in shooting 35mm but were put off by its costliness. They then turned to digital image capture as an option, until they realized how much latitude they would need in the highlights of their shots, given the volume of snow and the grayness of the skies in the places they were filming.

The choice to shoot on 16mm and the references drawn from Milton Avery’s paintings inspired Reichardt and Blauvelt to task Gasparro with finding a beige, brown-and-white look for the ranch, and his team scouted extensively to find the right space for this part of the film. Similarly, the parking lot photographs of Stephen Shore inspired Reichardt and Blauvelt to embrace the loneliness and emptiness of parking lots as a key element of their cinematic language. This subsequently influenced the colors in the costumes that Napier designed.

EMBRACING FORMALISM: NIGHT MOVES (2013)

By the late 2000’s, Reichardt was considered one of the standard-bearers for an American aesthetic of “Neo-Neo-Realism”, committed to an austerity in her visual approach that eschewed flair for unsparing character observation. She and Blauvelt’s style has become synonymous with contemporary slow cinema: long, unbroken takes and a patient editorial aesthetic that minimizes coverage.

Night Moves (2013) is a strong example of how the patience in Reichardt and Blauvelt’s working style made its way to the screen. After spending a year finding locations before production, Reichardt and Blauvelt had a strong sense of the color palette for the film, filling it with lush blues and greens based on the way the vegetation looked at different times of the year. Night Moves was the first film that Reichardt and Blauvelt shot digitally, but the change in capture techniques did not affect the approach they took to the camera operating and editing.

Blauvelt shot the film in a relatively strict formal style, with either locked-off static compositions or carefully executed dolly movements. This created an observational, minimalist tone that, in conjunction with Reichardt’s editing, allowed the film to feel like a simmering slow burn from start to finish.

EMBRACING SPONTANEITY: SHOWING UP (2023)

Although so much time goes into studying references, location scouting, working with other department heads and shot-listing prior to production, Reichardt and Blauvelt don’t storyboard, and almost never refer to their shot list on set. Their preparation serves as a means by which they can arrive on the same page about how they want to shoot, and from there, they remain open to blocking and shooting styles on set itself.

In Showing Up, Reichardt and Blauvelt treated the script and their visual approach as an evolving art form, allowing the details of how the actors behaved in the space to dictate their coverage on the day. The entire production was set up at the Oregon College of Art and Craft, but because the school was empty for the shoot, the filmmaking team had to re-create one from scratch. production designer Anthony Gasparro and the art team brought in a group of art teachers, students, and recent graduates to fill the space and turn it into an actively working creative environment. As the school developed organically, so did Reichardt and Blauvelt’s shooting plan. The script and the shot list evolved organically from day to day, constantly redesigned to capture the life and creative work of both the lead actors and background performers as it was happening before them.

When examining the work of Reichardt over the past decade plus, viewers feel a consistency and specificity of vision that binds this group of films together despite their wide thematic and tonal differences. That subtle but deeply felt sense of creative authorship in part due to the methodical development of a unique working relationship with fellow travelers like Blauvelt and is a testament to the benefits of long-term creative collaboration in the craft of filmmaking.

SOURCES

Roads to Nowhere, edited by Alex Heeney and Orla Smith, 2020

Filmmaker Magazine: Day for Night for Day for Night: DP Christopher Blauvelt on First Cow

Senses of Cinema: Countering Dominant Cinema: Temporality in Meek’s Cutoff

IndieWire: Professor Kelly Reichardt’s Filmmaking 101 Primer

The Directors Series: Kelly Reichardt’s “Night Moves”