02.21.23

HOW BLACK MUSIC MADE ITS WAY TO THE MOVIES

Black music has always been foundational to America’s musical and broader cultural identity. But at the turn of the 20th century, a revolution sparked. Black music artists finally began to gain widespread recognition for their work, and placed it on the forefront of the American and global music scene. The Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and 30s is often cited as a kicking off point for this shift, where Black artists demanded to be seen for their craft and forged their own path in America’s cultural landscape.

Black musical artists forged their own genres during this era. These genres gained widespread appeal, and the artists at their center dominated the attention of audiences. Across the century, Black-originated genres ranged from spiritual to jazz, blues, soul, R&B, afrofuturism, pop, hip hop, and many more. In many cases, these genres catalyzed and popularized musical movements that influenced artists from other cultures within the US and around the world. By the mid-1960s and 70s, film and television was starting to reflect the influence of Black music. Artists like Quincy Jones brought Black music into mainstream cinema through his hit song The Eyes of Love in the 1967 film Banning. The song also made him the first Black person to ever be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Song. Jones went on to arrange the soundtracks for some of the most recognizable films of the century, notwithstanding his longtime collaboration with artists such as Michael Jackson, Count Basie, and Miles Davis.

As Black music found its way into the mainstream on both the radio and in film, filmmakers started to celebrate their accomplishments across genres in the stories of their movies. Films foregrounded Black music in biographical dramas and historical fiction, in fantasy musicals and afro-futurist music videos. Today, music by Black artists is ubiquitous in world cinema, but their place in Black music films is significant for the technical and artistic innovations it has led to. The temptation for these music films could easily have been to focus on the music – but these films have defied conventions of the genre to go beyond the sound. The visual language of Black music films has been pushed time and time again by filmmakers telling stories of Black music. In this study, we will dive into the ways that films in different Black musical genres pushed the boundaries of cinema to evoke not only the sound, but the feeling of the music.

HOW PRODUCTION DESIGN BRINGS US INSIDE THE MINDS OF BLUES & JAZZ ARTISTS

Blues is a genre of music that originated in the Deep South of the United States in the 19th century, incorporating a wide range of musical traditions from African-American culture. Blues is often characterized by musical techniques such as call-and-response, the blues scale and specific chord progressions, and the influence of this music can be found in jazz, R&B, rock and roll, and many other genres.

Jazz is often cited as having first emerged in the Black communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th century. The genre has its roots in blues, and as it developed its own musical character, it spread around the world to become one of the most influential genres of the 20th century. Films celebrating icons of blues and jazz icons and featuring their music have been at the forefront of American culture since the mid-1940s. But as Black filmmakers have had increasing control of the movies telling stories about Black musicians, they have also innovated the form of music movies to go beyond the music. Production design has been a key tool through which filmmakers have been able to go beyond period accuracy – evoking the visceral headspace of the characters and bringing their music into the visual language of the film by tethering it to their emotional and psychological journeys. Here are some examples.

BESSIE is a 2015 biographical music drama about American blues singer Bessie Smith, and tells the story of her transition from a struggling young singer into “The Empress of the Blues”. The film was co-written and directed by Dee Rees and starred Queen Latifah as Smith, with supporting roles from Michael K Williams as Smith’s first husband Jack Gee, and Mo’Nique as Ma Rainey. Bessie was released on HBO and became the platform’s most watched original film in history, and won four Primetime Emmy Awards, including Outstanding Television Movie. Rees worked on the film with American Production Designer Clark Hunter, whose credits include Road Trip and Old School.

The pair wanted the design to track Bessie’s emotional arc through the film, with a monochromatic color palette dominated by wood textures during Bessie’s vaudeville days. After Bessie gets a recording contract and her career takes off, Hunter’s design is filled with bolder, brighter colors, before evening out to a more pastel color palette when things start to even out later in her life. Hunter’s work was based in research of the era, but was free to move beyond exacting period accuracy. The vaudeville theaters that were built and designed for the film were made on one hand to evoke the scale and glitz of the space, but also as a means of contrasting Bessie’s outward success with the challenges she faced in her private life. Hunter worked closely with costume designer Michael Boyd to start with research and then move away to allow the design to evoke the rollercoaster of human emotions in the characters, mixing exuberance with sensual elegance and quieter reality in equal measure.

MILES AHEAD is a 2015 American music biographical drama co-written, directed by and starring Don Cheadle in his feature directorial debut. The film interprets the life and music of jazz musician Miles Davis, and takes its title from Davis’s 1957 album. The film also stars Emayatzy Corinealdi and Ewan McGregor, and premiered at the New York Film Festival before grossing over $5 million worldwide. Cheadle worked on the film with American Production Designer Hannah Beachler, who is also known for her work on films such as Moonlight, Lemonade and Black Panther.

Cheadle and Beachler began their collaboration intent on a freeform approach to both the narrative and the production design, with time jumps and mixtures of camera strategy alongside a desire to embed Miles’s paranoid subconscious into the visual design of the film. Beachler allowed the design of the film to wear the influence of Blaxploitation films that influenced Miles, the way that Miles saw himself at times as a gangster, and the influence of drugs on his view of the world. Beachler and her team researched his actual home and decor for a base of the design of the film, but felt comfortable departing from it, using it as a visual sampling to get to the state of his mind. Sets were built to reflect his internal chaos, as well as depict his life in the era.

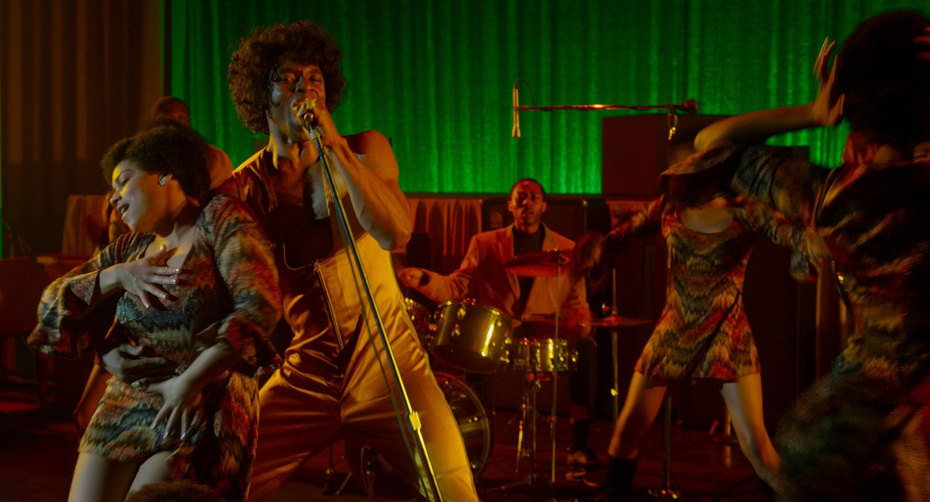

MA RAINEY’S BLACK BOTTOM is a 2020 American drama directed by George C. Wolfe and written by Ruben Santiago-Hudson, based on the 1982 play of the same name by August Wilson. The film stars Viola Davis as Ma Rainey, as well as Chadwick Boseman, Glynn Turman, Colman Domingo and Michael Potts. The film dramatizes a turbulent recording session of Ma Rainey’s in 1920s Chicago. Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom was nominated for five Academy Awards, winning in the Best Makeup and Hairstyling and Best Costume Design categories. Wolfe worked on the film with Production Designers Mark Ricker and Karen O’Hara.

Wolfe and Santiago-Hudson were intent from the script stage that they wanted the world of the film to be small, dark and intense, creating an atmosphere of claustrophobia in the audience and bringing them into the intensity of the music and the music-making process for Ma Rainey and her band. The room in which much of the film takes place had no windows with no external motivated light except for a tiny window high up and out of reach, trapping performers in the space along with the audience. The script called for a rehearsal space of minimal size with no air and no light, wanting to conjure up images of the bottom floor of a slave ship. Ricker and O’Hara built the set on stage in the 31st St Studios in Pittsburgh, and worked with cinematographer Tobias Schliessler to build entire lighting design around that solitary window, with tungsten fresnels and occasionally softening with diffusion frames for close ups, fill with a 12×12 softbox with Skypanels. Ricker and O’Hara did not have a lot of source material to work from, so they started with recording material like the machines and booths as a way of informing the design of the space. The pair limited the palette of the film as much as possible to get it as close to a black and white film as they could – evoking the period, but also the intensity of the space and time of the story.

USING THE CAMERA TO EMBRACE THE POETRY OF SOUL AND R&B

Rhythm and Blues music, otherwise known as R&B, originated in African-American communities during the 1940s. The term was originally used by record companies to describe all music marketed mainly to Black Americans in urban centers, but the style developed its own tropes and techniques out of its roots in jazz. Commercial R&B groups often featured bands of piano, guitar, bass, drums, saxophones and backing vocalists, and became one of the dominant genres of 20th century American music, as well as the foundation of rock and roll.

Soul music is a genre that originated amongst Black musicians through the mid-20th century, with origins in gospel music as well as R&B. Soul music has lived in a close relationship with R&B and rock and roll throughout its evolution, pioneered by artists such as Ray Charles, James Brown and The Temptations. Across the range of films made about soul and R&B music and its artists, the camera has been at the forefront of bringing musicality to cinema. Here are some examples of the ways that cinematography was used to construct a visual language that went beyond depicting reality with exacting accuracy – embracing the poetry of music and its relationship to the lives of the characters, and bringing the audience inside the music using composition, movement, framing and bold camera decisions.

GET ON UP is a 2014 American musical biographical drama about the life of James Brown, directed by Tate Taylor and written by Jez and John-Henry Butterworth. The film stars Chadwick Boseman as Brown, and also features an ensemble cast including Viola Davis, Nelsan Ellis, Dan Aykroyd, Craig Robinson and Octavia Spencer. Taylor worked on the film with South African cinematographer Stephen Goldblatt.

Taylor and Goldblatt decided early on to shoot in Mississippi in order to make the South a character, shooting in real locations that had been preserved since the early 20th century. Goldblatt pushed the camera to capture the film in vibrant colors, capture the feeling of the South and of Brown. Working in close concert with Costume Designer Sharen Davis, who considered herself closer to Brown’s stylist than to Boseman’s costumer, the pair created a color palette that was striking, aggressive and seductive, bringing out the elements of Brown’s character that they wanted the film to honor.

RAY is a 2004 American biographical musical drama following 30 years in the life of Ray Charles, played by Jamie Foxx. The film was directed by Taylor Hackford from a screenplay by James L. White, and also starred Kerry Washington, Clifton Powell, Harry Lennix, Richard Schiff and Regina King. The film grossed over $124 million from its $40 million budget, earning six Academy Award nominations and winning for Best Actor (Foxx). Hackford worked on the film with Polish cinematographer Paweł Edelman.

Hackford and Edelman considered the cinematography of Ray as containing three levels of reality. The primary level was the linear story of Ray’s life and career from when he boarded a bus in Florida 1948 to the end of his heroin addiction in 1965. Next was the flashbacks of Ray’s childhood, a loving but also tragic time when he lost his younger brother in a drowning accident, as well as his sight. Hackford and Edelman wanted to show this period with saturation, vibrance, happiness, rather than typical sepia / black and white treatment of the past, given the strength and joy of Ray’s memories of that time. The linear story was more contrasted but desaturated to feel the intensity of his experiences without sight, the nocturnal world he occupied, with Edelman using a bleach bypass-like process in the DI to evoke this look. The final level – Ray’s relationship with his mother via flashes of her memory in his head, were brief, hallucinatory passages. Once again opting to use the DI rather than in-camera techniques, Edelman went for a very blown-out look for these passages, bringing out the intensity of these memories and linking all three looks to the evolution of Ray’s music.

RESPECT is a 2021 American biographical musical drama directed by Liesl Tommy in her feature directorial debut, following the life of American singer Aretha Franklin (Jennifer Hudson). Forest Whitaker, Marlon Wayans, Audra McDonald, Marc Maron, Tituss Burgess and Mary J. Blige also star. The film won the Chairman’s Award at the Palm Springs International Film Festival (Hudson), as well as an NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Actress in a Motion Picture (Hudson). Tommy worked on the film with American cinematographer Kramer Morgenthau, whose filmography includes Thor: The Dark World, Chef and Creed II.

Tommy and Morgenthau wanted the camera in Respect to treat its music sequences like poetry rather than like dialogue, aiming to go beyond capturing the reality of concerts and performances, and instead get inside the heads of the people at the concert, and those putting it on. Morgenthau shot with the Arri Alexa LT with Panavision T Series lenses, using glass expressively alongside LUTs to maximize the emotional expressiveness of concert scenes. This film was rare in that the songs were done almost in their entirety, and had to be designed to cover the whole song, not just snippets, and make them feel both extraordinary and a part of the endemic visual language. Morgenthau placed emphasis on epicness, constantly using a floating camera that moved in 360 on cranes and steadicams, and building a lighting design that allowed for that strategy.

SUMMER OF SOUL (…OR, WHEN THE REVOLUTION COULD NOT BE TELEVISED) is a 2021 American documentary directed by Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson in his feature directorial debut, and follows the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival. The festival took place on six Sundays between June 29 and August 24 1969 at Mount Morris Park (now Marcus Garvey Park) in Harlem. Summer of Soul premiered at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival, where it won the Grand Jury Prize and the Audience Award in the documentary categories, before going on to gross over $3.5 million at the box office and winning the Best Documentary Feature at the Academy Awards. Thompson worked on the film with editor Joshua L. Pearson.

Summer of Soul was constructed out of professional footage of the festival that was filmed as it happened, stock news footage, and modern-day interviews with attendees, musicians, and other commentators to provide historical background and social context. But the visual resources the film had at its disposal were surprisingly limited. Where the Woodstock Music Festival of the same era had 15 16mm cameras shooting at all times, the Harlem Cultural Festival only had 5 cameras pointed at the stage. The challenge for Thompson and Pearson became how to make this experience immersive. The answer lay in embracing the limitations of the visuals, embracing the glitches, shots where the cameras were starting up etc., and leaning in poetry and abstractions to create immersive montages of the festival. Thompson and Pearson leaned into strange techniques of the time such as interview photos that had white borders painted around their figures before being re-photographed, as well as techniques like long video dissolves that would last over 4 seconds. By embracing the cinematography’s period idiosyncrasies, the pair created this film’s own idiosyncrasies, and captured the life of the world beyond the stage and the music.

BRINGING COLOR INTO THE VISUAL LANGUAGE OF MOTOWN

Few eras of American music have had more influence than Motown. Motown Records is an American record label owned by the Universal Music group, founded by Berry Gordon Jr. as Tamla Records in 1958. The term came from combining “motor” and “town”, referencing Detroit as the original headquarters for the label. Motown itself emerged as a style of soul music with mainstream pop appeal, and became the most successful subgenre and music label of the mid-20th century. During the 1960s, Motown achieved 79 records in the top ten of the Billboard Hot 100.

While Motown itself references the company and a sub-genre that sits within soul, the films of and about the Motown age have had a significant impact on American cinema. Common across them all is a vibrant use of color to capture the feeling of the music, the feeling of the time and place, and the glamor of the characters at the heart of Motown’s rise. Here are some examples.

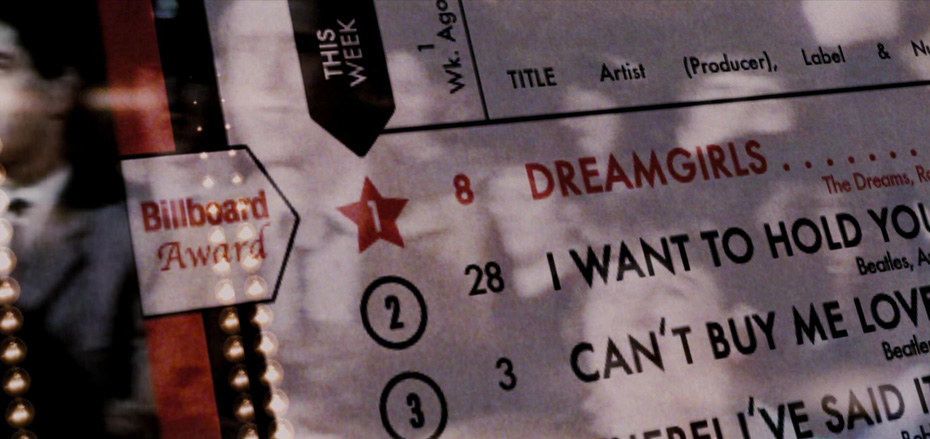

DREAMGIRLS is a 2006 American musical drama written and directed by Bill Condon, based on the 1981 Broadway musical of the same name. The film is a work of fiction that takes strong inspiration from the history of the Motown record label and the journey of the Supremes. In the film, we track the evolution of R&B and Soul music during the 1960s and 70s through the eyes of a Detroit girl group known as The Dreams, and their manipulative record executive. Jamie Foxx, Beyoncé Knowles, Eddie Murphy, Danny Glover, Jennifer Hudson, Anika Noni Rose and Keith Robinson star. Dreamgirls grossed over $155 million from its $75-80 million budget, earning eighth Academy Awards and winning for Best Supporting Actress (Hudson) and Best Sound Mixing. Condon worked with German cinematographer Tobias Schliessler.

Schliessler and Condon wanted the cinematography of Dreamgirls to create a language that moved from reality to musical and back organically. Color was vital to this effort, and to conveying as much story as they needed to in such a short space of time. Red in particular was important to the visual language of the film, highlighting Curtis’s step into the dark side. During that transitional point of the film, heat lamps were used to light the dance rehearsal scene, while lights coming through the window were pushed to be a little cooler than daylight to really feel it. This scene was match cut to a stage scene, following the Dreamettes making their entrance in red. Schliessler followed them moving towards the light low from behind to emphasize the drama of the moment, the emotion of this transition, and used red lights on the stage and in the costuming to signal through color that the emotional tenor of the film was moving towards darkness.

SPARKLE is a 2012 American musical film directed by Salim Akil and co-written by Mara Brock Akil and Howard Rosenman, based on the 1971 film of the same title. The film is also inspired by the journey of the Supremes, and follows three teenage sisters who start a girl group in the late 1950s in Detroit, during the Motown era. The film stars Jordin Sparks in her feature debut, as well as Whitney Houston, Derek Luke, Cee Lo Green, Mike Epps, Carmen Ejogo, Tika Sumpter, and Omari Hardwick. Sparkle grossed over $24 million from its $14 million budget and its soundtrack debuted at number 1 on the Billboard Soundtracks chart. Akil worked on the film with cinematographer Anastas Michos.

Akil and Michos worked closely with colorist John Persichetti to capture and accentuate the boldness of Detroit in the 1960s, not just in look, but in feel and in music. Persichetti leaned into certain color combinations typical of the era such as olive green rugs and red lights. But he also also wanted to recreate the feeling of the smokey nightclubs of Detroit in the 60s. Persichetti faced the challenge of how bright footage sometimes was, and let some of the dark areas go really dark in the DI, even to the point of not seeing the audience, instead letting the color tell that story atmospherically. Persichetti, Michos and Akil used color to help give the film a big budget look. That extended to giving the actresses big budget looks and making them pop out of the frame in their glamorous close ups, isolating details to achieve consistency in skin tones, and even desaturating costumes to allow their faces to pop, and embracing the differences in their skin tones.

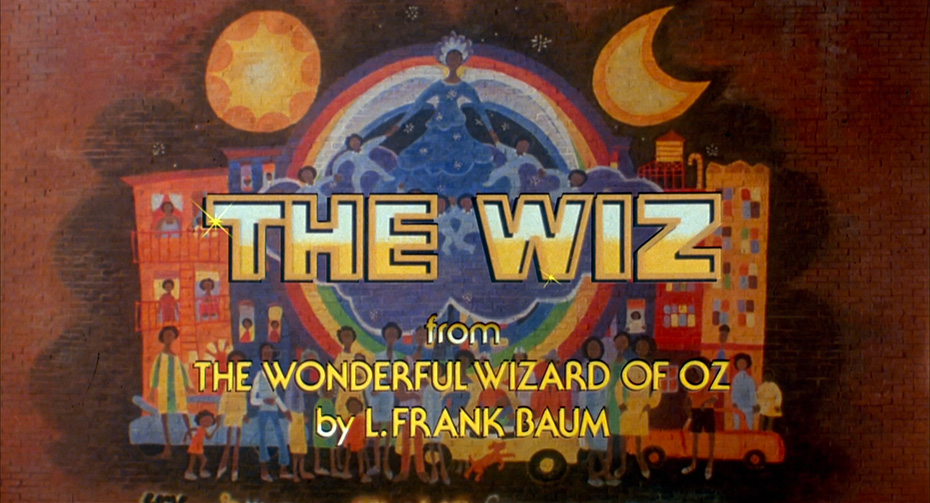

THE WIZ is a 1978 American musical fantasy adventure film directed by Sidney Lumet, adapted from the 1974 Broadway musical of the same name. It is a reimagining of Frank Baum’s 1900 novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz featuring an all-Black cast. Diana Ross stars as Dorothy, and the cast also features Michael Jackson (in his feature debut), Nipsey Russell, Ted Ross, Mable King, Theresa Merritt, Thelma Carpenter, Lena Horne and Richard Pryor. The Wiz did not succeed commercially upon its release, but drew critical praise including four Academy Award nominations. Today, the film is a cult classic, and one of the most well-known cinematic entries from the 1970s. Lumet worked on the film with British cinematographer Oswald Morris.

Color was used in The Wiz for the literal, emotional and storytelling journey of the characters. The story and its emotions could be tracked from the gold scene to the green scene, to the red scene and the emerald scene. The progress in colors told the progress of the characters through the story, and camera and design departments worked in sync to saturate the frame and bring color to the forefront. For the emerald scene, Morris used low key lighting with bright emerald glaciers on the sides to build anticipation, lighting vault doors strongly. He and his team brought in high key lighting design once the vault opened, changing the colors of the lights from green to gold to red in a psychedelic overload.

COSTUMING AFROFUTURISM: MUSIC, FANTASY AND REBELLION

While the term “afrofuturism” began as a way of referring to Black science fiction, it is today considered a more broad cultural aesthetic, philosophy of science and view of history that explores the relationship of the African diaspora with science and technology, and covers multiple forms of expression including design, science, art, music and film. Afrofuturist work has been similarly expansive in its scope and ambitions, capturing musicality, drama and politics in equal measure. Costuming has long been a core component of afrofuturist film, and in the case of Black music films living in the afrofuturist genre, costumes have become a tool of conveying musicality, as well as politics and rebellion, pushing the limits of accepted reality and offering visions of better alternatives. Here are some examples.

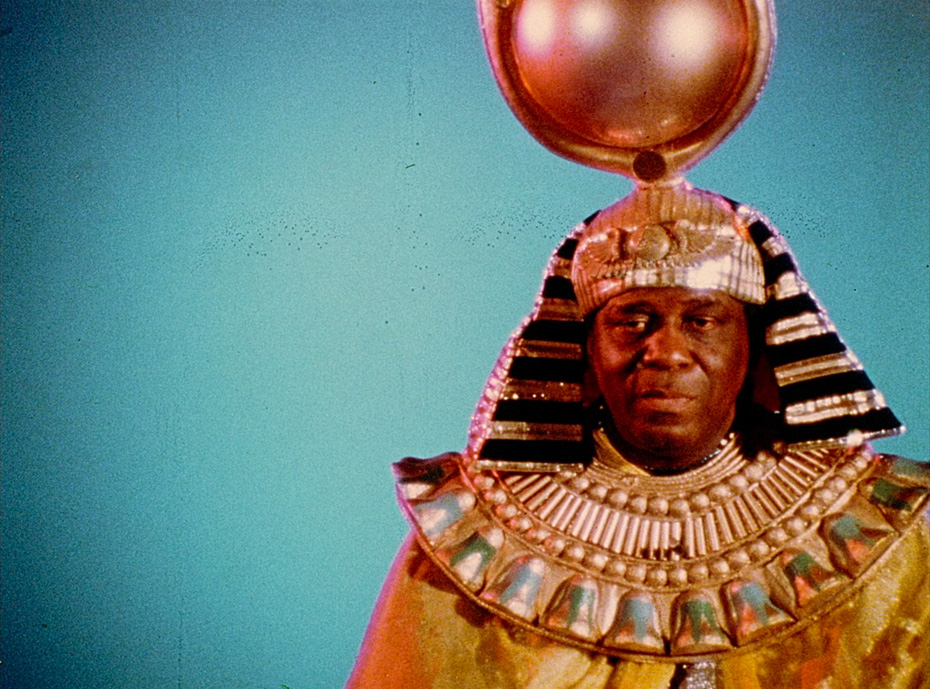

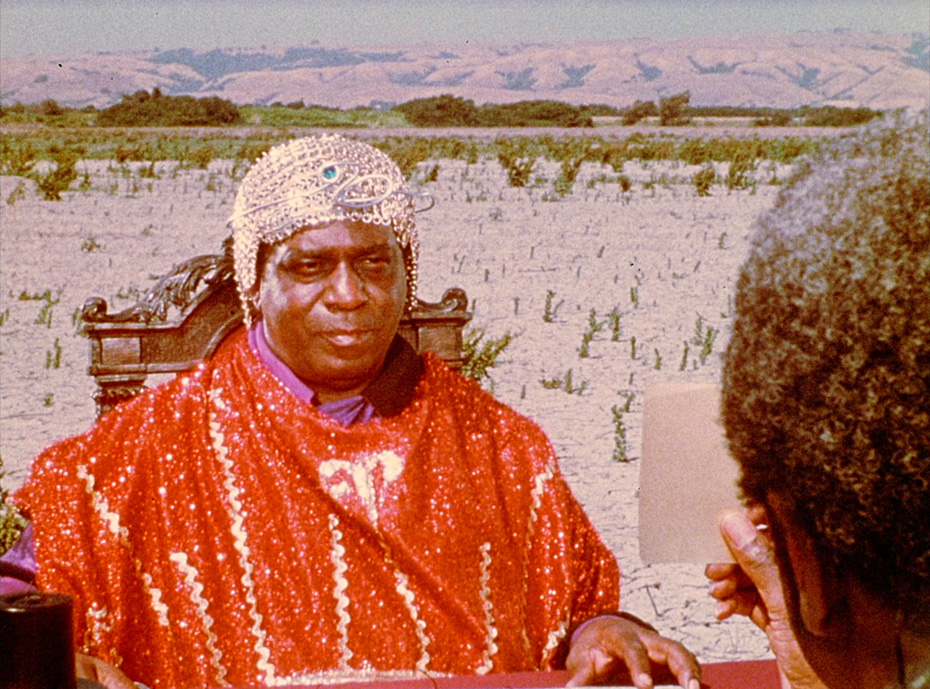

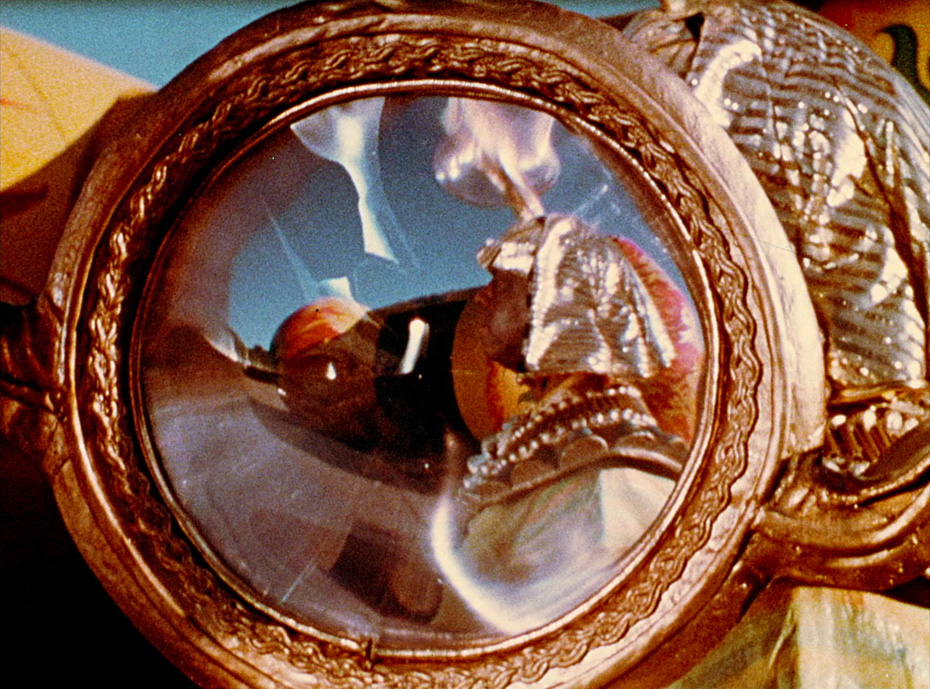

SPACE IS THE PLACE is a 1974 Afrofuturist sci-fi film directed by John Coney and written by Sun Ra and Joshua Smith, starring Sun Ra and his Arkestra, as well as Raymond Johnson. The film follows Sun Ra, the space age prophet who lands his spaceship in Oakland, having been presumed lost in space. Space is the Place is widely considered today to be a landmark of the afrofuturist canon in film.

Sun Ra says in the film: “Costumes are music. Colors throw out musical sounds.” The quote reflects the belief of the film that costume is music and political statement in equal measure, rejecting Eurocentric philosophies, and bringing back outer space costumes inspired by Egypt. Ra is covered in metallic capes, tunics embroidered with symbology and headdresses decorated with coins and metal chains, pushing color to the limit. The costumes embrace asymmetry, taking cheap, populist fabrics and infusing them with meaning through their remixing for the film. In doing so, the film offers an alternative to life that exceeds the limits of present existence, and also brings music into the film visually.

DIRTY COMPUTER is a 2018 musical sci-fi film, and the visual companion to Janelle Monáe’s third studio album of the same name. Billed as an “emotion picture” the film tells the story of an android, Jane 57821, and her attempts to break free from the constraints of a totalitarian society that forcibly makes her comply with its homophobic beliefs. The film was received to critical acclaim upon its release, and was widely seen as a groundbreaking entry in the visual album genre.

Monáe wanted the film costumed as an emotion film, expanding the horizons of the black queer experience. Monáe’s looks transition in the film alongside the music and as a counterpoint to it, making political and musical statements in one go. Monáe starts out with her hair in wrapped bantu knots with linked braids coming out the side, with a rainbow palette to her makeup. In “Crazy, Classic, Life”, she juxtaposes feminine and masculine, wearing a studded leather choker with a matching leather jacket over a delicate white tutu and punk rock accessories, including an afrocentric pair of earrings. In “Django Jane”, she is costumed in a militia uniform wearing a Kente Kufi, expressing Black female and queer militarism, while in “Pynk”, Monáe’s costume is boldly literal, embracing pink, femininity, and boldness through its saturation.

NEPTUNE FROST is a 2021 sci-fi romantic musical film co-directed by Saul Williams and Anisia Uzeyman, and starring Cheryl Isheja, Elvis Ngabo and Kaya Free. The film follows the relationship of Neptune and Matalusa, coltan miners in Burundi whose love leads a hacker collective. Neptune Frost gets its title from a Black Revolutionary soldier who served in the 1775 Continental Army. The film premiered at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival in the Directors Fortnight section. Williams and Uzeyman worked on the costumes of the film with Rwandan multidisciplinary artist Cédric Mizero.

Williams, Uzeyman and Mizero wanted to see the future through the costumes of Neptune Frost, critiquing the present and embracing musicality in equal measure. Neptune is escaping the shackles of the gender binary, while Matalusa is escaping labor exploitation and resource pillaging. Mizero wanted the costumes to be rooted in the present while projecting into the future. Costumes were eccentric, DIY and unashamedly musical. Neptune’s costumes break the fourth wall, including a head enclosure that looks like planetary rings. The gardening woman wears white frocks that feel like they float with sculptural head cones, and Matalusa’s jacket is made from black keyboard letters. For the characters of Neptune Frost, boldness is music and is politics, and ultimately, it is rebellion.

FILMING THE WORLD OF HIP HOP, NOT JUST ITS CHARACTERS

Hip hop originated in New York City in the 1970s as a genre influenced by Black music of the past and popular music across the world. It has become both a musical genre and a culture as it has expanded, and is today arguably the most ubiquitous genre of popular music anywhere in the world. Hip hop has influenced its own subgenres in film and television, and covers a broad spectrum of visual styles and genres. In the following examples, we look at films that used cinematography to create an aesthetic style that placed as much importance on understanding the characters and their world as it did on capturing the music they produced.

HUSTLE & FLOW is a 2005 American drama written and directed by Craig Brewer, and produced by John Singleton and Stephanie Allen. It stars Terrence Howard as DJay, a hustler and pimp who aspires to be a rapper. The film also stars Anthony Anderson, Taryn Manning, Taraji P. Henson, Paula Jai Parker, Elise Neal. DJ Qualls and Ludacris. Hustle & Flow premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, where it won the Audience Award and the Excellence in Cinematography Award. It went on to gross over $23 million from its $2.8 million budget, and was nominated for Academy Awards in the Best Actor (Howard) and Best Original Song (Three 6 Mafia’s “It’s Hard out Here for a Pimp”) categories. Brewer worked on the film with American cinematographer Amy Vincent, whose credits include Eve’s Bayou, I Heart Huckabees and A Million Ways to Die in the West.

Brewer and Vincent almost immediately arrived at a common set of visual references for Hustle & Flow built around the work of Mississippi photographer Birney Imes, whose photos of juke joints in Mississippi became a crucial element of grounding the visual language in the reality of the world. Vincent shot the film on 16mm, paying homage to the 1970s, and embracing grain as a visual technique for bringing the audience inside the reality of the world, with honest portrayals of characters and their lives which were free from the stereotypes commonly associated with them.

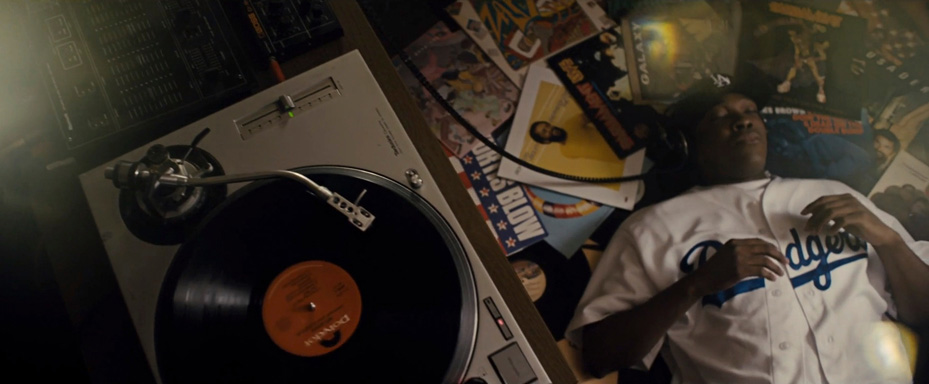

STRAIGHT OUTTA COMPTON is a 2015 American biographical musical drama directed by F. Gary Gray, depicting the life of the hip hop group N.W.A. and its members Eazy-E (Jason Mitchell), Ice Cube (O’Shea Jackson Jr.), Dr. Dre (Corey Hawkins), MC Ren (Aldis Hodge) and DJ Yella (Neil Brown Jr.). Paul Giamatti also stars as N.W.A. ‘s manager Jerry Heller. Straight Outta Compton grossed over $201 million worldwide from its $28-50 million budget, earning an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Screenplay, and spawning a soundtrack album that debuted at number 1 on the Rap Albums chart. Gray worked on the film with American cinematographer Matthew Libatique, whose credits include Iron Man, Black Swan and A Star is Born.

Gray and Libatique surprisingly did not have a lot of reference material outside images of NWA and some images of LA at that time, and made the decision to be very faithful to the time and place that those images evoked. Libatique wanted to build a shooting style that evolved over the course of the film. The film would begin with the feeling that someone was in the room with the characters holding a camera. There weren’t many close-ups, and the camera was usually hand-held. Libatique shot on the RED Dragon with Kowa anamorphic lenses, creating a dirty and gritty look for the opening acts of the film. As N.W.A.’s star rises, the cinematography evolves. Libatique switched to Zeiss Super Speeds to add sheen to the film when the band starts playing for big audiences, and evolved the camera movement away from hand-held work towards more shots with steadicam and spydercam.

REDEFINING HOW MUSIC LOOKS, AND HOW IMAGES SOUND

Black music redefined American culture through the 20th century, and by the end of the century, it had redefined cinema. But films about Black music have time and again recognized the potential to do more than just play songs for the audience. Regardless of the genre, the time period or the characters being followed, films about Black music have allowed the sound to shape the image, and to bring musicality into the visual language of the movie. They have redefined the way that music looks, and the way that images sound.