THE TUESDAY DROP – 5/25

05.25.21 / New Shots

PHANTOM THREAD (2017)

First up is Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2017 romantic drama PHANTOM THREAD. Serving as his own cinematographer (Gaffer Mike Bauman was credited as the Lighting Cameraman), Anderson set out to make a period film that carried a distinctively different look from the more glossy, “beautiful” period pieces made for film and television at the time. By underexposing his film stock and then pushing it, filling the sets with theatrical haze and smoke, and using antique lenses, Anderson was able to give the film a unique, textural feel that sets Phantom Thread apart from most other period pieces.

THE FRENCH CONNECTION (1971)

Then we have William Freidkin’s 1971 action thriller THE FRENCH CONNECTION, starring Gene Hackman and Roy Scheider. The winner of five Academy Awards, including Best Picture (and the first R-rated Academy Award winner), the film has become a landmark in 1970s New York cinema. Cinematographer Owen Roizman captured a grittiness and harshness in New York City that would go on to be a hallmark for New York auteurs such as Sidney Lumet and Martin Scorsese. Made on a shoestring budget, Freidkin and Roizman often had to resort to tactics such as stopping their cars on the Brooklyn Bridge to create a traffic jam, and bringing a wheelchair into subway stations to film dolly shots. This, combined with the grain they generated from having to push their 100 ISO film stock, created a strikingly authentic portrait of 1970s New York.

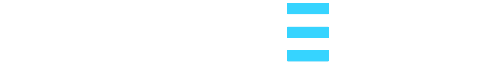

TOUKI BOUKI (1973)

Next we have TOUKI BOUKI, Djibril Diop Mambety’s 1973 drama from Senegal. Made on a budget of just $30,000, Touki Bouki has become one of the most iconic films to have come out of West Africa. Characterized by its vivid, avant-garde images, cinematographers Pap Sama Sow and Georges Bracher managed to blend the surreal and the naturalistic into a synthesized whole. Though the camera itself rarely moves in this film, the dynamism created by the unconventional use of camera position, as well as the movement within almost every frame, creates an explosive, poetic portrait of a couple dreaming of running away to Paris.

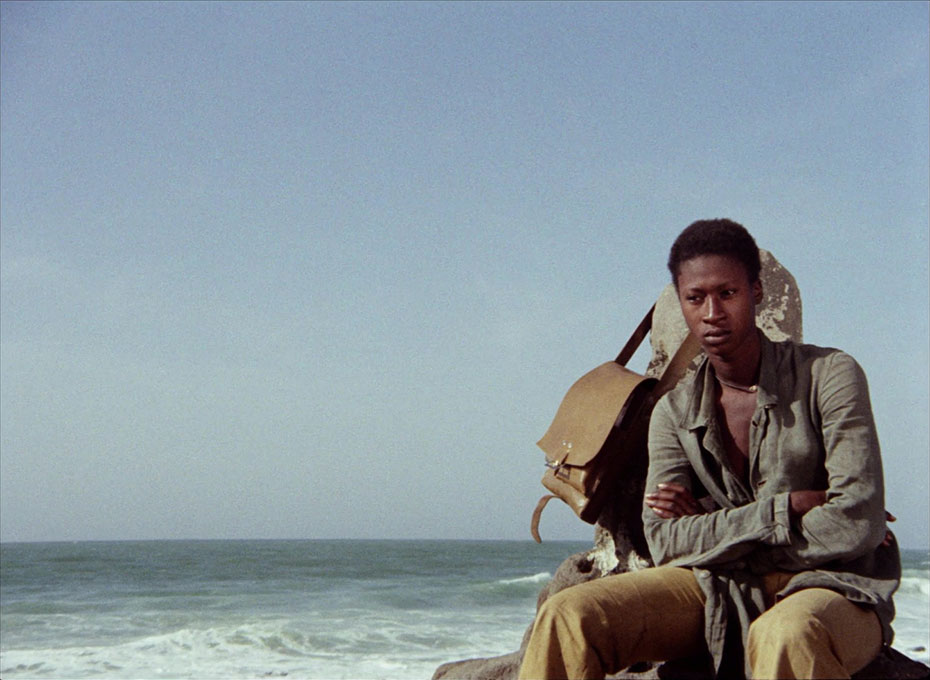

COOL HAND LUKE (1967)

Next we have the 1967 prison drama COOL HAND LUKE, starring Paul Newman and directed by Stuart Rosenberg in his feature film debut. Cool Hand Luke was the 10th film that legendary cinematographer Conrad Hall photographed, and to this day it remains one of his most recognized. It was on this project that Hall began to experiment with “imperfections“ as a way of communicating a more gritty and naturalistic sense of reality – a critical departure from the norm of aiming for perfection and beauty in cinematography. By embracing unconventional camera movement and lens flares, Cool Hand Luke communicates the harshness of the prisoners’ conditions, putting the audience in the mindset and viscera of its protagonist.

SAINT MAUD (2020)

We also have SAINT MAUD, the debut psychological horror film from British writer/director Rose Glass. Cinematographer Ben Fordesman, who won the award for Best Cinematography at the 2020 British Independent Film Awards, creates a moody, understated visual style that accentuates the terror of the film’s supernatural moments. References such as Persona, Repulsion and Rosemary’s Baby informed the film’s tonal approach, and Fordesman lit the film with consistently high contrast ratios in both day and night, creating highly composed shots that feel almost like still photographs. The result is a film that uses religion as a unique device in a genre that often deals with questions of faith.

SHAUN OF THE DEAD (2004)

Next is Edgar Wright’s second feature film, SHAUN OF THE DEAD. Written with star Simon Pegg, Shaun of the Dead is another example of Wright’s interest in taking tropes of genre films and using them to subvert the audience’s expectations, often to comedic effect. Cinematographer David M. Dunlap creates both slow, threatening moments in long steadicam tracking shots, as well as sequences filled with crash zooms that hurtle the audience along as quickly as possible, putting us on edge throughout the movie.

JENNIFER’S BODY (2009)

Then we have the 2009 comedy horror JENNIFER’S BODY, written by Diablo Cody and directed by Karyn Kusama. Initially dismissed by critics, the film has since become a feminist cult classic that upends the expectations of the male gaze. Cinematographer M. David Mullen worked with Kusama to create a look for the film that he described as “moody naturalism,” using Brian De Palma’s horror classic Carrie and the photography of Todd Hido as references. The result is a film that takes a small-town high school story to a place that is darkly comic, unsettling and memorable.

REBECCA (1940)

Next is Alfred Hitchcock’s 1940 romantic psychodrama REBECCA. An adaptation of Daphne du Maurier’s novel of the same name, Rebecca was the first film Hitchcock made in America. Photographed by George Barnes, and the winner of the 1941 Academy Award for Best Black and White Cinematography, Rebecca is still considered by many to be one of Hitchcock’s most elegant films. A particular highlight is Hitchcock’s ability to create the lavish Manderley estate inside the studio sets through a combination of miniatures and matte paintings – visual effects that still hold up over 80 years later.

THE FAVOURITE (2018)

Then we have Yorgos Lanthimos’s 2018 period comedy, THE FAVOURITE. The Favourite marked the first collaboration between Lanthimos and Irish cinematographer Robbie Ryan, who had up until then been mostly known for his work with British filmmaker Andrea Arnold. The Favourite was a dramatic shift in visual style for Ryan, who shot this film mostly on a 35mm lens with the occasional 6mm fisheye lens, and almost entirely with natural light. The punctuation of whip pans, long, fluid shots and slow motion creates a visual style that constantly surprises its audience, pushing a story that might otherwise have been a polite chamber piece into a provocative, darkly comic period film.

GIRLHOOD (2014)

Finally, we have Celine Sciamma’s 2015 coming-of-age drama GIRLHOOD. Cinematographer and frequent collaborator Crystel Fournier, who also shot Sciamma’s films Water Lilies and Tomboy, wanted to create a cool atmosphere with warm counterpoints. Sciamma and Fournier also experimented with pushing the limits of “realism” in their colors, using lamps with high color temperatures or LEDs instead of tungsten or sodium vapor bulbs to light night scenes. They also pushed the look of the film in terms of aspect ratio, choosing to shoot Girlhood in cinemascope with anamorphic lenses in order to tell the story of the four girls in an aspect ratio that could contain them together.