THE TUESDAY DROP – 01/11

01.11.22 / New Shots

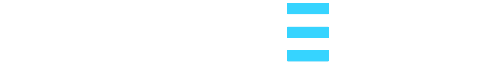

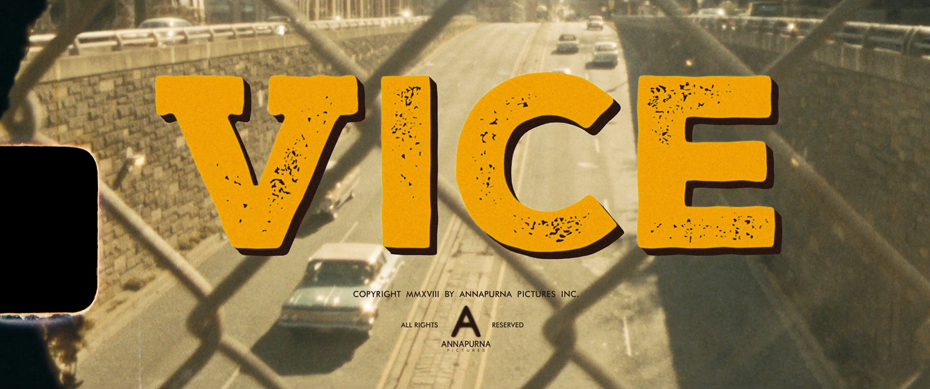

VICE (2018)

VICE is a 2018 biographical political black comedy-drama written and directed by Adam McKay and starring Christian Bale as former US Vice President Dick Cheney. The film also stars Amy Adams, Steve Carrell, Sam Rockwell and Jesse Plemmons, and follows the life of Cheney with particular focus on his time as Vice President to George W Bush. Vice was nominated for eight Academy Awards, including Best Editing, Best Actor, Best Director and Best Picture, winning for Best Make-up and Hairstyling. McKay worked on Vice with Australian cinematographer Greig Fraser, who was best known at the time for his work on Bright Star, Killing Them Softly, Zero Dark Thirty and Lion.

McKay and Fraser decided on a collaged approach to the visual language of the movie, opting to shoot on both 16mm and 35mm celluloid in a variety of different formats, with different cameras and lenses to represent the different periods across this five decade story. Fraser shot with the Kodak Vision 500T and 200T stocks on multiple different cameras, including the Arriflex 235, the Arricam LT, the Arriflex 416, Eyemos and more. From a lighting perspective, Fraser kept the film consistently lit with LED fixtures, opting for their flexibility and lighter footprint on set to quickly and flexibly light scenes that involved complex multi camera setups.

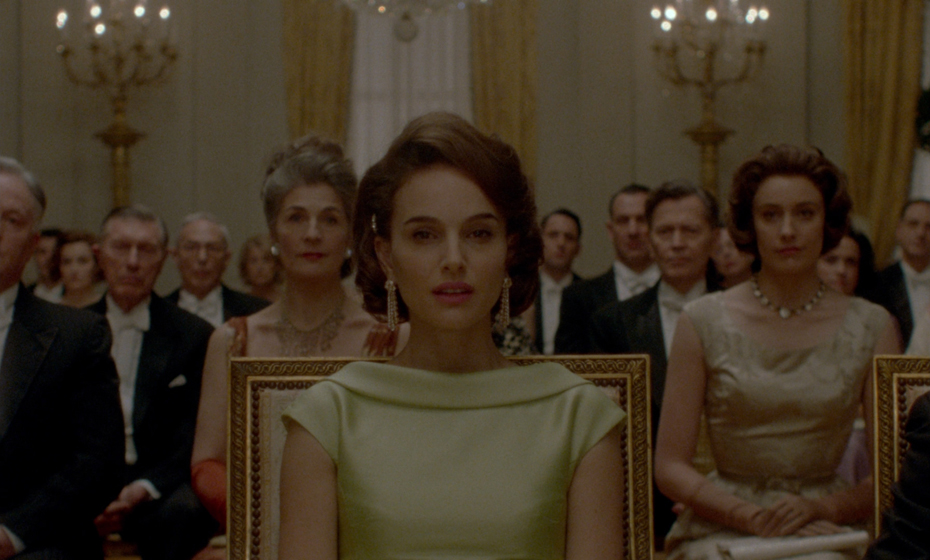

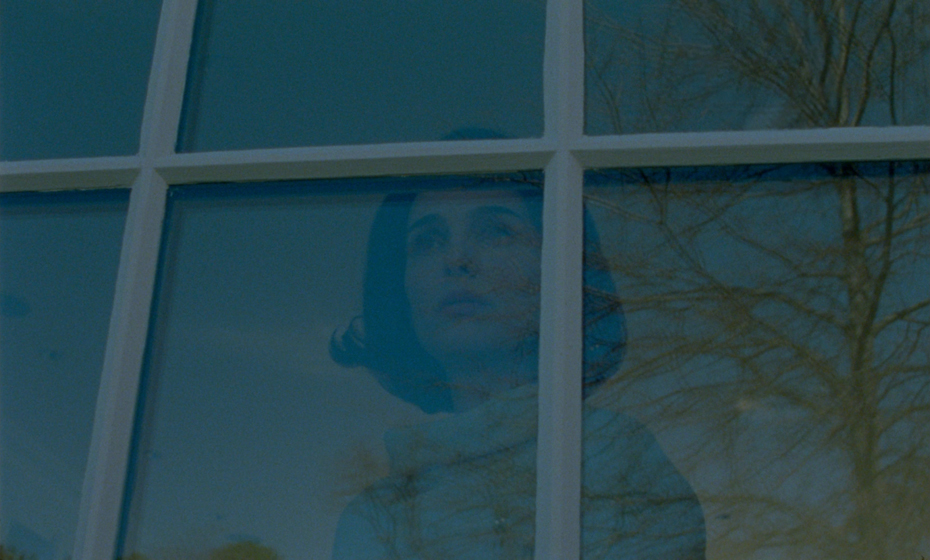

JACKIE (2016)

JACKIE is a 2016 biographical drama written by Noah Oppenheim and directed by Pablo Larraín. The film stars Natalie Portman as former US First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, and follows her life immediately after the assassination of her husband, President John F. Kennedy. Jackie won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, and was nominated for Best Actress, Best Original Score and Best Costume Design at the Academy Awards. Larraín worked on the project with French cinematographer Stéphane Fontaine. Fontaine was best known at the time for his work with Jacques Audiard on films such as The Beat That My Heart Skipped, Rust and Bone and A Prophet. Larraín and Fontaine decided to shoot Jackie largely using 16mm film, on Kodak 7219 and 7213, in order to give the film a strong color palette with noticeable grain.

The movie was mostly shot on the sound stages at Cité du Cinéma in Saint-Denis, north of Paris, using an Arri 416 package and Zeiss Super Speed lenses. With over 2 months to prepare the film, Larrain ensured that key rooms of the White House as well as Air Force One were painstakingly recreated on the sound stage. They also decided to shoot the film almost entirely handheld using wide lenses (14mm, 18mm and 25mm). Larraín and Fontaine wanted a sense of immediacy and intimacy with Jackie as she went through this key period in her life, while not sacrificing the scale of the high-powered surroundings she found herself in at that time. Finally, Fontaine and his longtime gaffer, Xavier Chollet, wanted to create a lighting language that used lights that were as soft as possible, almost to the point where there were no shadows at all, giving the entire movie an airy, almost dream-like quality.

KNIVES OUT (2019)

Rian Johnson’s fifth feature film, KNIVES OUT, is a 2019 murder mystery-comedy that follows a master detective named Benoit Blanc as he investigates the death of the patriarch of a wealthy, dysfunctional family. The film features an ensemble cast starring Daniel Craig, Chris Evans, Ana de Armas, Jamie Lee Curtis, Christopher Plummer, Don Johnson, Toni Collette, Lakeith Stanfield and Katherine Langford. Knives Out premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. Johnson worked on the film with longtime collaborator Steve Yedlin, who he had worked with on all of his previous features.

Johnson had first told Yedlin about the concept over ten years ago, but only wrote the script closer to production itself. The pair agreed on a look for the film that they called “theatrical realism”, aiming for each scene’s look to be organically motivated, but heightened. Johnson and Yedlin wanted to create a photographic look that balanced the tone of a comedic “whodunnit” and a dark drama about toxic privilege and class conflict. The film strikes a balance between the exuberant and luxurious with a tone of noir-ish chiaroscuro. Yedlin shot the film on the Alexa Mini using Panavision zoom lenses, wanting zoom-ins and outs to be a core part of the visual language. Yedlin wanted the movie to be full of compound camera moves, combining dollies with pans and zooms to heighten the action in a way reminiscent of Robert Altman films.

THE THEORY OF EVERYTHING (2014)

THE THEORY OF EVERYTHING is a 2014 biographical romantic drama directed by James Marsh, following the life of theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking, and adapted from the memoir of his ex-wife Jane Hawking, which detailed her relationship with him, his professional success, and his diagnosis of ALS. The film stars Eddie Redmaybe and Felicity Jones, and was nominated for five Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Actor and Best Actress. Marsh worked on The Theory of Everything with French cinematographer Benoît Delhomme. Delhomme was best known at the time for his work on films such as The Scent of Green Papaya, The Merchant of Venice and Lawless.

Marsh and Delhomme set up a visual language with the camera that put the audience in the perspective of Stephen Hawking, hinging on his time before and after his diagnosis of ALS. In the first part of the film, the camerawork was free-flowing, with lots of movement and longer shots, filmed with Leica Summilux spherical lenses. After Hawkings’s diagnosis, the movie was shot in still frames, and with Hawks anamorphic lenses. From a lighting standpoint, Delhomme and Marsh were clear that they did not want a typical British “kitchen sink” look for the movie. Delhomme decided to turn the setting of Cambridge into a vivid, almost Californian-style university campus, creating a vibrancy that captured the intelligence of its central characters, and that cut against the tone of the film, particularly when Hawking learns of his diagnosis.

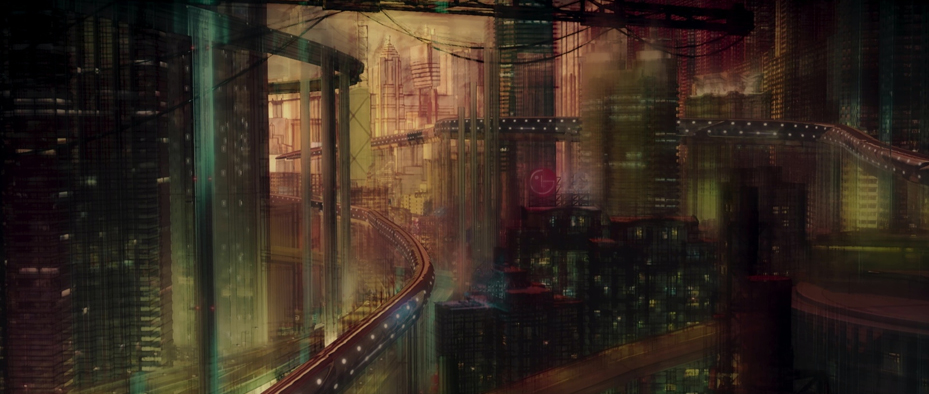

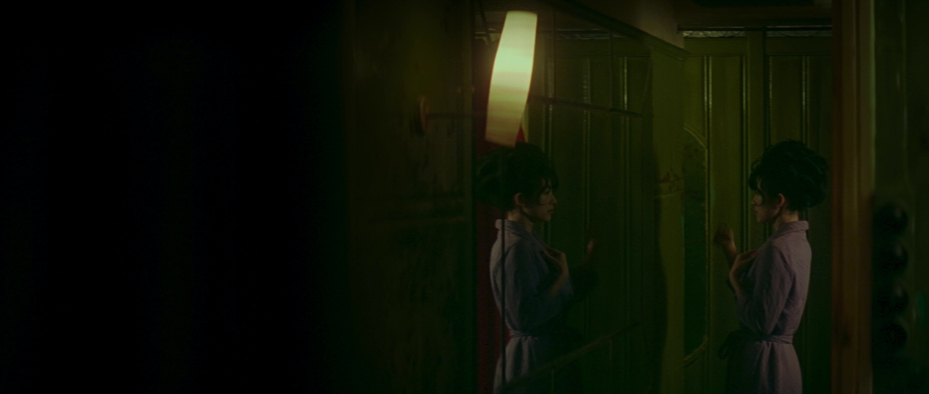

2046 (2004)

2046 is a romantic drama written, produced and directed by Wong Kar-wai. It is a loose sequel to Days of Being Wild and In the Mood for Love, and follows the aftermath of Chow Mo-wan’s unconsummated affair with Su Li-zhen. The film stars Tony Leung, Maggie Cheung, Gong Li and Faye Wong, and was nominated for the Golden Palm at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival. Wong worked on 2046 with longtime collaborator Christopher Doyle. Doyle and Wong had worked together on both Days of Being Wild and In the Mood for Love, as well as on Ashes of Time, Chungking Express, Fallen Angels and Happy Together.

Wong approached 2046 inspired by elements of science fiction, with the futuristic setting of 2046 being a place where people go to recover lost memories. But with a stop-start production period that lasted over five years and that involved re-shoots and re-edits as the shoot went along, Doyle also relied on Kwan Pun-leung and Lai Yiu-fai to shoot the movie. Doyle and Wong once again pushed the visual language of the film into unconventional territory, with very shallow depth-of-field close ups, off-balance compositions and mirrors used to create multiple perspectives on the same subject in the cinemascope frame commonplace.

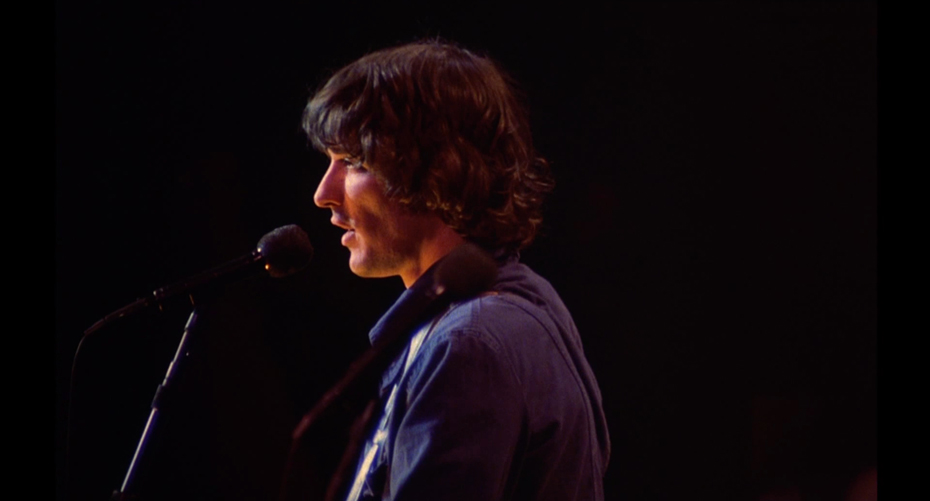

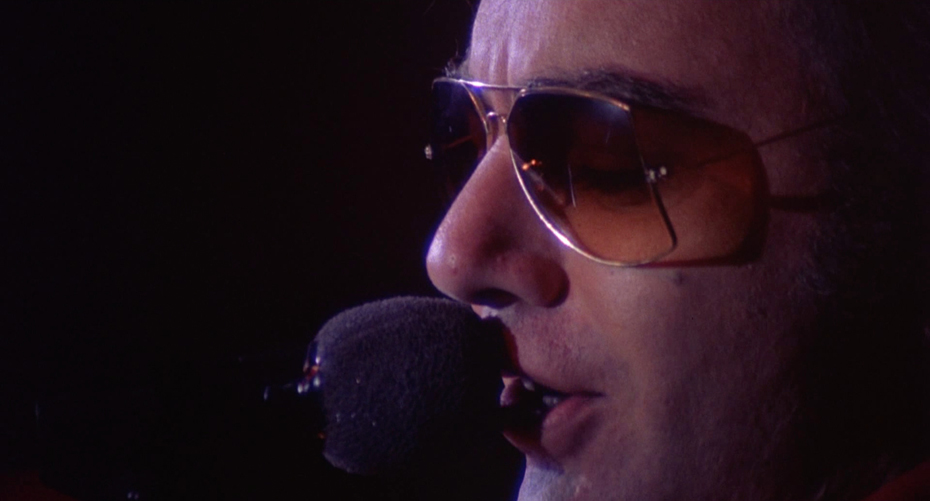

THE LAST WALTZ (1978)

THE LAST WALTZ is a 1978 concert documentary film that covers the farewell concert of Canadian-American rock group The Band, which was held on November 25, 1976 at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco. The documentary was directed by Martin Scorsese, who was introduced to The Band frontman Robbie Robertson by Jonathan Taplin, the producer of Mean Streets. The Last Waltz was initially intended to be shot on 16mm film, but under Scorsese’s guidance, the film grew to a full 35mm production with a 24-track recording system – making it the first rock film to have this scale of production with either camera or audio. Scorsese hired West Side Story and The Sound of Music production designer Boris Leven to design the stage and lighting of the Winterland Ballroom, and amassed a troupe of cinematographers and camera operators to capture the concert.

The lead cinematographer was Michael Chapman, with additional cinematography by Bobby Byrne, László Kovács, David Myers, Hiro Narita, Michael W. Watkins, and Vilmos Zsigmond. The cinematographers and camera operators were all on a shared headphone system with Scorsese as they executed the shots which Scorsese had meticulously storyboarded. At one point, Zsigmond got so tired of Scorsese’s constant instructions that he took off his headset – ironically making him the only camera operator rolling during Muddy Waters’s performance of “Mannish Boy” (Scorsese ordered a film reload by mistake at this point). The film also almost fell apart during the concert itself, when Bob Dylan decided to back out of the documentary (Warner Bros. only agreed to finance the film on the condition Dylan would be in it). After Bill Graham negotiated with Dylan, he agreed to let Scorsese shoot his last two songs, saving the film. The film was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress in 2019, and is considered one of the greatest concert films ever made.

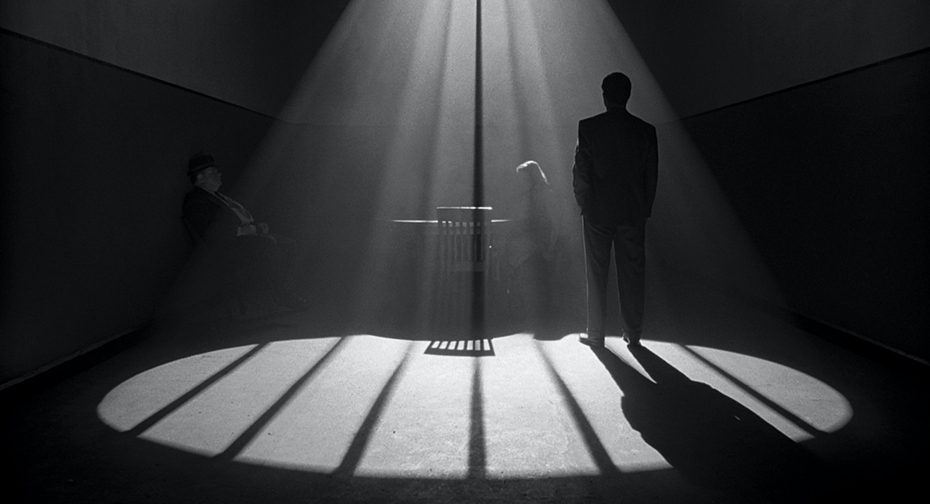

THE MAN WHO WASN’T THERE (2001)

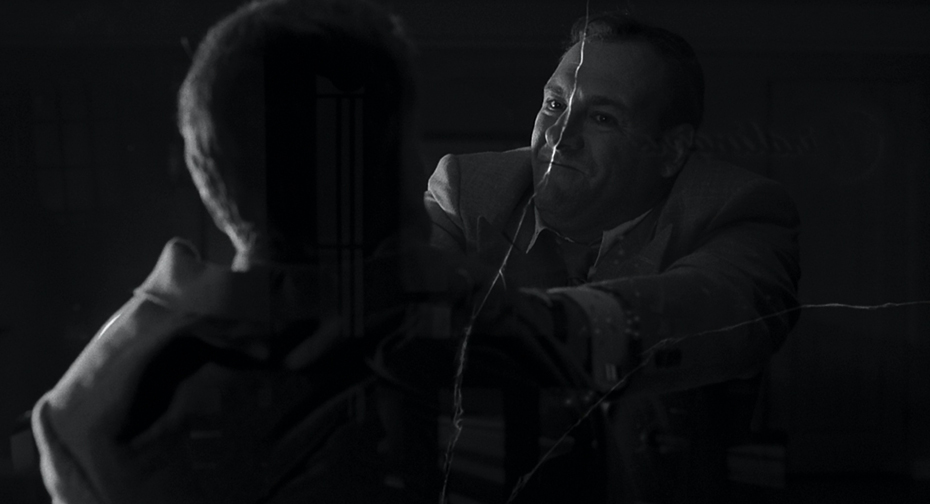

THE MAN WHO WASN’T THERE is a 2001 crime film written, directed and produced by Joel and Ethan Coen. The film stars Billy Bob Thornton as a chain-smoking barber named Ed Crane, who plans to blackmail his wife’s boss (who she is having an affair with) for money to invest in a dry cleaning business. The film also stars Frances McDormand, James Gandolfini, Richard Jenkins, Scarlett Johansson and Jon Polito. The film won the Best Director Award at the 2001 Cannes Film Festival, and was nominated for Best Cinematography at the Academy Awards. The Coen brothers worked on The Man Who Wasn’t There with British cinematographer and frequent collaborator Roger Deakins.

One of the first decisions they made together was to shoot the film in black and white, more to capture the atmosphere of their small town Northern California setting than to explicitly capture the mood of film noir. However, since they were obligated to create a color master for foreign markets, the Coens and Deakins shot the movie in color and converted it digitally to black and white, making it the first US studio feature to be entirely color-corrected using digital methods. Deakins spent almost two months on the process, and in doing so became a pioneer for digital color correction, now a fundamental process in contemporary filmmaking.

TO THE WONDER (2013)

Terrence Malick’s sixth feature film, TO THE WONDER, is a romantic drama starring Ben Affleck, Rachel McAdams, Olga Kurylenko and Javier Bardem. The film chronicles the lives of a couple, Neil and Marina (Affleck and Kurylenko) who, after falling in love in Paris, struggle to keep their relationship together in the United States, particularly after Neil reconnects with a childhood sweetheart (McAdams). To the Wonder premiered at the Venice Film Festival, where it was nominated for the Golden Lion award. Malick worked on the film with Mexican cinematographer Emmanuel Lebezki. Lubezki and Malick had previously collaborated on The New World and The Tree of Life. They approached To the Wonder with an aim of creating a more cinematographic approach to filmmaking that separated itself from traditional practices.

The pair shot the film on a combination of 35mm and 65mm film – 35mm for the scenes with Affleck and Kurylenko in Oklahoma, and 65mm for when Affleck and McAdams’s characters are together. They wanted a clean look for the film with rich frames, and shot with spherical lenses in a 2.35:1 aspect ratio. Lubezki and Malick also wanted to shoot with minimal lighting equipment, allowing them to shoot flexibly, and to shoot a lot of footage as well. While the pair prepared extensively, they also wanted to capture moments spontaneously, and would often improvise moments or go to new locations during the shoot. The result is a movie that is often more like a contemplation than a traditional, plot-driven story, and the visual language captures this mood throughout.

THE GENTLEMEN (2019)

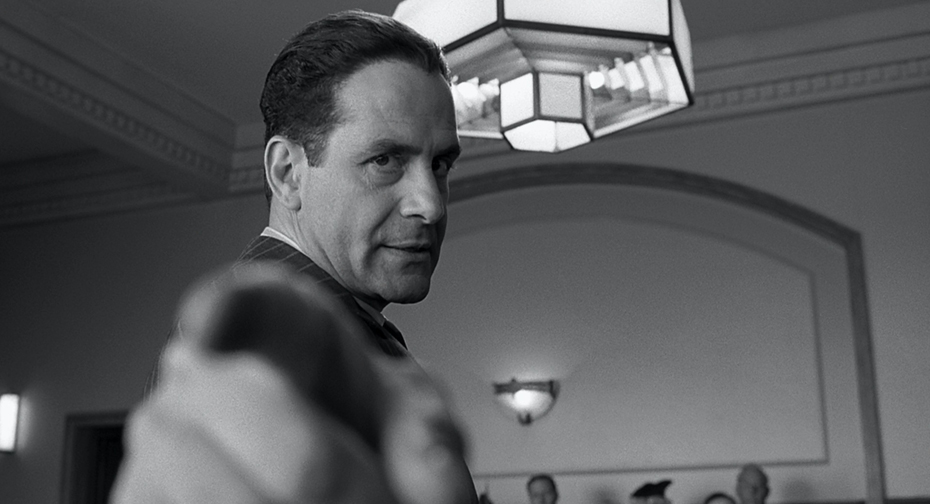

Guy Ritchie’s 11th feature film, THE GENTLEMEN, is an action comedy following an American marijuana kingpin in England who inadvertantly sets off a chain of violent schemes from criminals who want to steal his business when he decides to sell it. The film stars Matthew McConaughey, Charlie Hunnam, Henry Golding, Michelle Dockery, Jeremy Strong, Eddie Marsan, Colin Farrell and Hugh Grant. Ritchie worked on The Gentlemen with British cinematographer Alan Stewart, who he had collaborated with on Aladdin. Stewart had also worked as the Second Unit DP on Ritchie’s Sherlock Holmes films.

Ritchie and Stewart decided to shoot The Gentlemen on the Arri Alexa XT Plus with Panavision Primo and Angenieux Optimo lenses. They wanted to create a classical visual language for the film that mirrored the characters at the heart of the story, and presented an update to classic English gangster movies. Stewart lit the film with a lot of stronger overhead sources, casting some shadows under the eyes of the characters but also creating bounce light off surfaces such as tabletops. Given that the majority of the film was shot on sound stages, VFX work was needed to bring some of the film’s iconic London settings to life, as well as to extend some of the sets such as the marijuana farm that McConaughey’s character runs.

MONA LISA SMILE (2003)

MONA LISA SMILE is a 2003 drama directed by Mike Newell and starring Julia Roberts, Kirsten Dunst, Julia Stiles and Maggie Gyllenhaal. It follows Katherine Watson (Roberts), a recent UCLA graduate hired to teach art history at the prestigious all-female Wellesley College in 1953. Watson is determined to confront outmoded beliefs of society and pushes her students to challenge the stereotypes they are expected to conform to. Newell worked on Mona Lisa Smile with American cinematographer Anastas N. Micos.

Newell, Micos and the producers obtained permission from Wellesley College to shoot the movie on location at the university’s campus. Micos and Newell wanted to create a flowing visual language for the movie where shots could evolve from close ups to wides and vice-versa. They wanted the film to also capture a certain nostalgia for the period, and to romanticize the endeavors of Watson in her environment. Backgrounds in the distance and outside windows were often allowed to blow out in order to create a halo-like glow around the characters, and characters in indoor settings were often lit in a classical manner reminiscent of Hollywood studio films of the era.