04.18.23

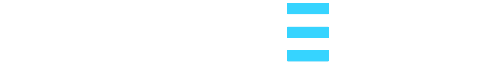

THE SECRETS OF HENRY SELICK

Animation owes a lot to Henry Selick. One of the most innovative and experimental filmmakers of his generation, Selick’s work helped bring stop-motion filmmaking into the 21st century, while his experimentation with mixing live-action and animated sequences paved the way for some of the most groundbreaking films of the past thirty years. His work has pushed the technological possibilities of the medium and inspired generations of live-action, animation and mixed-media filmmakers to come.

In this article, we will take a survey of Selick’s career, from his influences and education, to his early short films, to the groundbreaking work of his most well-known feature films.

EARLY INFLUENCES & EDUCATION

Selick was influenced by stop-motion cinema from an early age. The first film that Selick saw in theaters was The 7th Voyage of Sinbad – a technicolor fantasy adventure film directed by Nathan Juran featuring Ray Harryhausen’s full color widescreen stop-motion animation technology Dynamation. The stop-motion-animated cyclops became a pivotal image in Selick’s mind, inspiring his love for the medium.

After studying at Rutgers and Syracuse Universities, and playing in a rock n’ roll band for several years, Selick decided to take his interests in animation more seriously and enrolled at CalArts, where he was one of the only students in his cohort (alongside students like Brad Bird and John Lasseter) to study both the Disney-led character animation program as well as Jules Engel’s experimental animation program. The experimental animation program introduced Selick to world animation, puppet animation from Eastern Europe, work made by the Canadian film board, and many other styles. While at CalArts, Selick made the short films Phases and Tube Tales, both of which have since been preserved by the Academy Film Archive.

After CalArts, Selick went to work with animator Glen Keane at Disney, learning drawing and classical staging first-hand while working on films such as The Great Mouse Detective and Who Framed Roger Rabbit. Selick also made a short film of his own, Seepage, during this time. Selick was excited about the progress he was making as an animator but unsatisfied with the films he was working on, and eventually left Disney in search of a new creative start in the Bay Area.

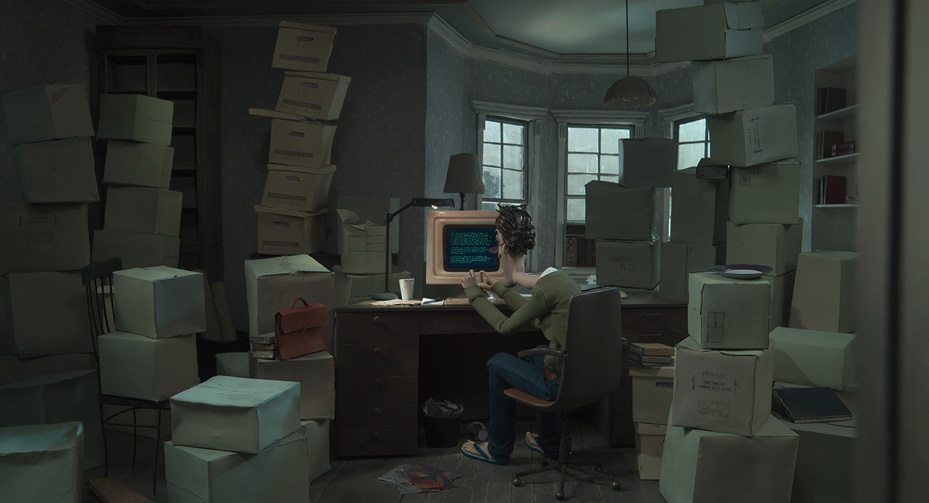

Soon after Selick moved to Northern California, he began working for MTV, where he was given significant creative freedom to make work in his own style. It was here that he made his 1991 short film Slow Bob in the Lower Dimensions, which follows Robert Potemkin, a man who lives in the attic of his family’s house. One night, his sisters, who are siamese twins, plan a prank on him, but before they can, sentient lizards send him to a parallel world to save photo-people. Slow Bob in the Lower Dimensions was originally conceived by Selick as a pilot proposal episode, but the series was never ordered.

Slow Bob in the Lower Dimensions was created through a combination of live-action, computer-generated animation and 2D photo-based stop-motion animation. The mix of styles became a calling card for Selick, and though the series was never made, the short film garnered attention for his idiosyncratic style and his formal experimentation with film media. Selick also met American cinematographer Peter Kozachik working on Slow Bob in the Lower Dimensions. Their collaboration went on to pave the way for one of the most important creative partnerships of both of their careers, eventually shooting three feature films together.

Shortly after Slow Bob in the Lower Dimensions, Selick received a phone call from an old classmate from CalArts, who wanted to revive an idea from his grad school days with Selick in the director’s chair. The classmate was Tim Burton, and the film was The Nightmare Before Christmas.

The Nightmare Before Christmas was initially conceived as a 30 minute television special when Burton pitched it to Disney, but after some development work, Disney decided that the project was too strange to belong on their slate. After Burton moved into live-action films and started having success, he revived the project as a feature film and brought Selick on to direct. Selick and Burton began making the film before there was a finished script, convinced of the premise and the practical and technical approach they wanted to take in filming it.

The Nightmare Before Christmas was a fairly traditional stop-motion animated film by Selick’s standards, with almost all the effects done in camera (with the exception of some CG snow at the end of the film). Animation began in July 1991, and Selick assembled a crew of over 120, with 230 sets being used on over 20 individual sound stages during photography. 227 puppets were constructed for the characters, and over 109,000 individual stop-motion frames were captured.

Selick wanted the journey through the film to be mirrored visually by a clear shift in visual tone and artist influence, referencing artists from Ray Harryhousen, Francis Bacon, Wassily Kandisky to Ladislas Starevich and more. Selick wanted Halloween Town to convey the influence of German Expressionism, Christmas town to recall a Dr. Seuss set piece and the “Real World” to be “plain, simple and perfectly aligned.”

Selick, cinematographer Peter Kozachik, and their team opted to create the characters’ expressions using replacement faces. This was a technique invented by George Palin, where each expression of the character and every in-between was designed, built and painted so that teams could manipulate the character’s shifting emotions with absolute precision. The gravity-defying stop-motion elements of the film were also traditionally accomplished, using Spiderwire – a mesh so thin that it doesn’t photograph clearly, allowing the characters to be attached to it in specific poses as they were captured frame by frame flying through the air.

JAMES AND THE GIANT PEACH (1996)

After the success of The Nightmare Before Christmas, Tim Burton reportedly persuaded Disney to spend $2 million to acquire Roald Dahl’s classic children’s novel James and the Giant Peach for Selick to adapt. Selick took the opportunity afforded from the success of his previous film to push James and the Giant Peach into more experimental territory, bringing live-action sequences as book-ends to the stop-motion animation, and experimenting with CG techniques in some of the animated sequences.

After convincing Disney of the necessity to include both live-action and stop-motion techniques, Selick and cinematographer Peter Kozachik went about conceiving of a visual language and style that could cohesively hold the two together. They decided that the live-action elements should be stylized and cartoony, and the color palette should be pushed towards grays and greens. Once James enters the animation world, the palette expands to be filled with rich and beautiful hues, highlighting the magic of the world James enters, and recalling films such as The Wizard of Oz.

Unlike The Nightmare Before Christmas, Selick and his team animated the faces of the puppets using posable faces – wire skeletons covered in a silicone skin that had to be hand-manipulated to change expressions. What was lost in precision and repeatability of expressions was made up for in need for fewer puppets and a more hand-made feel to the facial movements of the characters.

CORALINE (2009)

After working with Disney on The Nightmare Before Christmas and James and the Giant Peach, Selick directed the 2001 film Monkeybone, which also combined live-action and stop-motion components. The film was not a critical or commercial success, and after its release, Selick moved on and started working with Oregon-based stop-motion animation company Laika, just starting up at the time. Selick and Laika began their partnership working together on the short film Moongirl (2005), about a boy who ends up on the moon while fishing one night and works with a girl to repair the moon. The film won the Special Jury Prize at the Ottawa International Animation Festival, and its success paved the way for one of the most influential animated films of its decade four years later, Coraline.

Coraline follows the titular character (voiced by Dakota Fanning) who discovers an alternate world behind a secret door that closely mirrors her own, but in many ways seems better – until she discovers its sinister secrets. The film grossed over $124 million from its $60 million budget, making it the third-highest grossing stop-motion animated film of all time. In the years since its release, Coraline has grown a huge cult following, and has become a landmark animated film of the 21st century so far.

It was critical to Selick and cinematographer Peter Kozachik that they build a visual language which would subtly communicate the differences in the worlds that Coraline occupies. They wanted the film to have more nuance and delicacy than other stop-motion films they had worked on and seen, with more precision and psychology built into the lensing and lighting choices. On one hand, they wanted to make these distinctions in color, depth of field and lensing. The fantasy world of the film was built with bigger sets, more colors and shot with wider lenses than the real world. But Selick and Kozachik then wanted to subtly turn the fantasy world into a nightmare without resorting to obvious techniques. It was for this reason that they chose to shoot Coraline in 3D, making it the first ever stop-motion film shot this way.

Seeing in 3 dimensions comes from the distance between your eyes (“interocular distance”), which creates different images that the brain can then interpret as depth. The same principle applies to shooting a 3D film. Because of the small scale and the stop-motion nature of Coraline, Selick and Kozachik couldn’t get cameras or lenses small enough to accomplish this. Instead, they created the interocular distance needed for a 3D image in stills, using motion controllers to move the cameras a precise amount for each individual frame, capturing a left eye shot and a right eye shot each time. This technique allowed Selick and Kozachik to control and manipulate the interocular distance between left and right eye over the course of the entire film. What started as a more “normal” 3D image gradually became more intense and unpleasant, creating the “breathing” effect in the latter parts of the film and turning a fantasy image imperceptibly into one that reflected Coraline’s nightmarish state of mind.

WENDELL & WILD (2022)

Selick began working with Jordan Peele and Keegan Michael-Key to develop Wendell & Wild in 2015, eager to embrace a rougher, more hand-made aesthetic of stop-motion animation that pushed away from the saturation of glossy computer-generated animation they were seeing. The film follows devious demon brothers Wendell and Wild, who enlist the help of 13-year-old Kat Elliot to summon them to the Land of the Living.

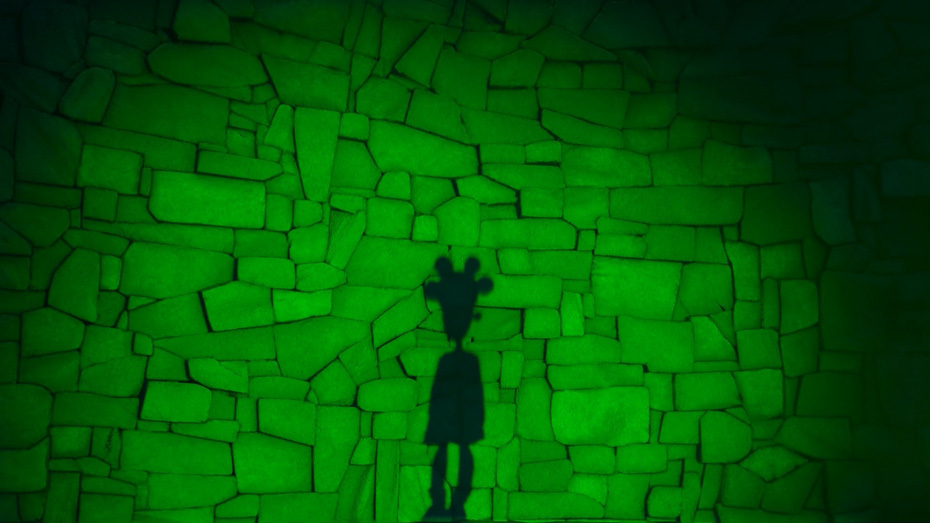

Selick was eager to retain the 2D look of the concept art by illustrator Pablo Lobato, and the animation team leaned further into the rough, unpolished aesthetic by cutting down on the in-between faces that they built for the characters. Wendell and Wild had more flat faces designed for the world of the dead and more dimensional ones for the world of the living, and a more expressionist version of the siblings was built for their first encounter with Kat, when they appear in a nightmare as giant floating heads and hands. Inspired by a YouTube video of a finger puppet, Selick and animation supervisors Malcolm Lamont and Jeff Riley built 12-inch silicone faces that were hollowed out and hand armature pieces poked into their eyebrows and around their mouths, allowing those features to be wildly exaggerated to create a haunting but comic surrealist effect.

Selick, Lamont and Riley did accept that CG would have some advantages in creating the look they were after for a sequence where they wanted to visualize a memory of Kat’s through shadow puppet-like projections. Rather than building hundreds of additional replacement faces for flat individual cut-out faces, the animation team built CG stop-motion faces without in-betweens, allowing the sequence to be animated as though it was a physical stop-motion sequence without the physical production and labor needed to stage and capture it in real life.

Few filmmakers in any medium have been as bold and experimental with form and technique on large-scale projects as Henry Selick. His early days experimenting with live-action and stop-motion in the same film have carried a strong throughline throughout his work, taking him from surrealist comedies to family adventure stories and children’s horror in equal measure. His technical innovations have paved the way for a new, more expressive approach to contemporary animation, and his style and stories have made him one of the most impactful animators of his generation.

SOURCES

NYT – Ray Harryhausen, Whose Creatures Battled Jason and Sinbad, Dies at 92

A.Frame – Henry Selick: 5 Movies That Inspired My Career in Animation

Academy Film Archive – Henry Selick

Museum of the Moving Image – Henry Selick

Letterboxd – Slow Bob in the Lower Dimensions

Far Out Magazine – The Painstakingly Long Production of ‘The Nightmare Before Christmas’

Cinefantastique – James & The Giant Peach

Ottawa International Animation Festival – Moongirl

IndieWire: ‘Wendell & Wild’: How Henry Selick’s Jordan Peele Team-Up Redefines Stop-Motion Animation