02.07.23

WHAT IS THE BLAXPLOITATION MOVEMENT?

The Blaxploitation era was a short-lived but hugely influential movement in American cinema, defining a new era for independent films in the early 1970s. Blaxploitation was born as a subgenre of the wider grindhouse film movement. Grindhouses were movie theaters that played films that “more respectable” theaters would not. They became hugely popular through the late 1960s and 70s, especially in major cities, and movies made explicitly to be shown in grindhouses created a number of popular film subgenres, often labeled under the term “exploitation” cinema.

Exploitation cinema was geared towards making movies at low costs, attempting to maximize financial gain by setting stories in sensationalized, often violent and sexual topics and contexts. Exploitation films were often shot fast and cheap, and though the level of quality fluctuated greatly from production to production, the racy subject matter made these films a big box office draw for the grindhouse theaters. Nowhere was this more prominent than in Blaxploitation films.

Blaxploitation is sometimes considered a movement in conversation with “Third Cinema”, a term first coined by Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino in 1969. They termed First Cinema as Hollywood and Second Cinema as the cinema of the bourgeoisie. Third Cinema to them was “the decolonization of culture.” Blaxploitation movies were largely made by Black filmmakers, first and foremost for Black audiences, and were hugely influenced by the American Civil Rights movement.

Blaxploitation movies took the racist tropes and stereotypes associated with Black characters and flipped the narrative or the perspective on those characters. They took figures such as pimps, drug dealers and sex workers and placed them at the center of the narrative, making them the heroes of the story. These characters were usually positioned against avatars of “the man” – white characters symbolizing or actualizing systems of oppression and violence against Black Americans. For the first time, movies had Black heroes who were willing to fight for their rights and use violence themselves, satisfying a demand that Black audiences had for their portrayal on screen.

The term Blaxploitation was originally used pejoratively. The term was coined in 1972 by Junius Griffin, then president of the Hollywood–Beverly Hills chapter of the NAACP. Critical of the subject matter of the films, the perceived glorification of violence, substance abuse and misogyny, these films had a complicated relationship with Black Americans and wider audiences at the time. On one hand, Blaxploitation movies had strong aesthetic and ideological ties to the Black Power movement and to organizations like the Black Panthers. But on the other hand, some people felt that they reinforced negative images and stereotypes about Black Americans.

Over 200 Blaxploitation films were made in under a decade. Though they were made for Black audiences first, the films had huge nationwide appeal, making millions at the box office and creating a new age of independent filmmaking in America. Though it was a short-lived era, it has had a massive social and aesthetic influence on American cinema. Its stories, characters and techniques redefined the mainstream image of Black people in popular culture, and ushered in an era of cool that low-budget filmmaking had never seen before.

HOW BLAXPLOITATION MOVIES MADE COOL FOR CHEAP

Blaxploitation movies often explored themes of crime, fighting back against “the man”, sex and Black American life of the time, but they were never confined by rules of style or genre. Blaxploitation movies went just as far into the horror genre (through movies such as BLACULA) as they did into comedy (through movies such as DOLEMITE) and women-led revenge stories (through movies such as CLEOPATRA JONES). But across almost all Blaxploitation movies was a bold visual aesthetic of innovation that gave audiences a portrait of Black life never seen before on screen. The low budgets of these films (films were rarely made for more than $500,000) inspired filmmakers to take visual risks that became part of the fabric of American pop culture.

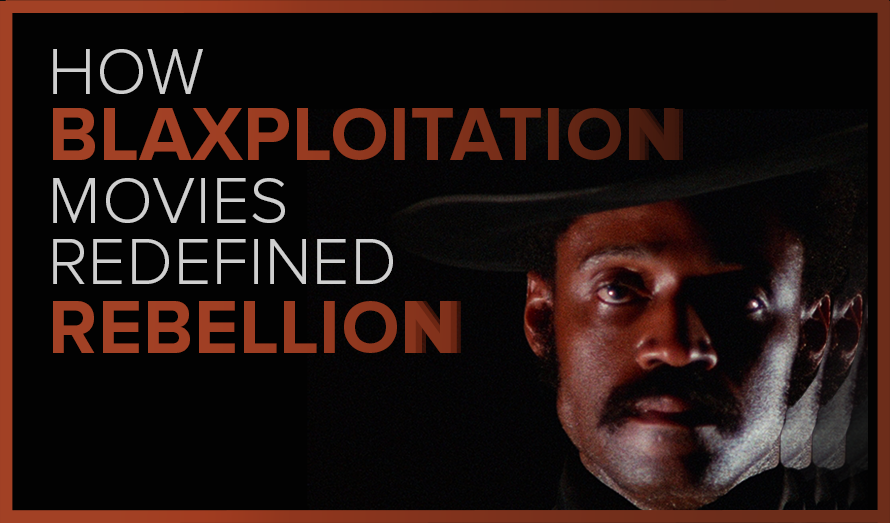

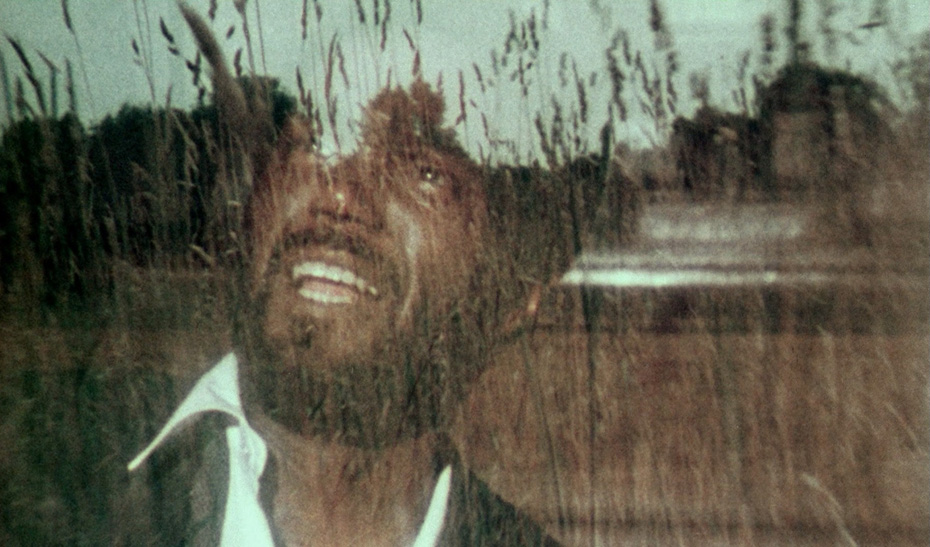

Many credit the 1971 film SWEET SWEETBACK’S BAADASSSSS SONG as the birth of the Blaxploitation movement. Written, produced, scored, edited, directed by and starring Melvin Van Peebles, the film follows Sweet Sweetback, a Black prostitute who, after saving a Black Panther from racist police and being accused of a crime he didn’t commit, goes on the run from “the man” aided by his community and some disillusioned Hells Angels. Van Peebles self-financed the project with the help of some loans after walking away from a three-picture deal with Columbia, determined to make a film on his own terms. Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song grossed over $15 million from its $150,000 budget. Upon its release, the film became required viewing for members of the Black Panther Party, and in 2020, it was inducted in the US National Film Registry by the Library of Congress.

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song created an iconic Blaxploitation hero, defined by his cool, tough demeanor and his sexual escapades. But arguably what attracted audiences most to the film was its unflinching political stance. Van Peebles created a character and a film that was willing to make revolution its subject both in substance and in style. Along with American cinematographer Robert Maxwell, who also shot Don’t Play Us Cheap, Van Peebles pushed Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song to its visual extremes, filling the movie with confronting editing patterns, unconventional camera angles, kaleidoscopic superimpositions, double exposure and saturated and clashing lighting designs. Van Peebles wanted to make a low-budget independent film that “looked as good as anything one of the major studios could turn out”. In doing so, he and his crew defied their production limitations, tiny budget and 19 day shooting schedule to create a bold visual language never before seen in American cinema.

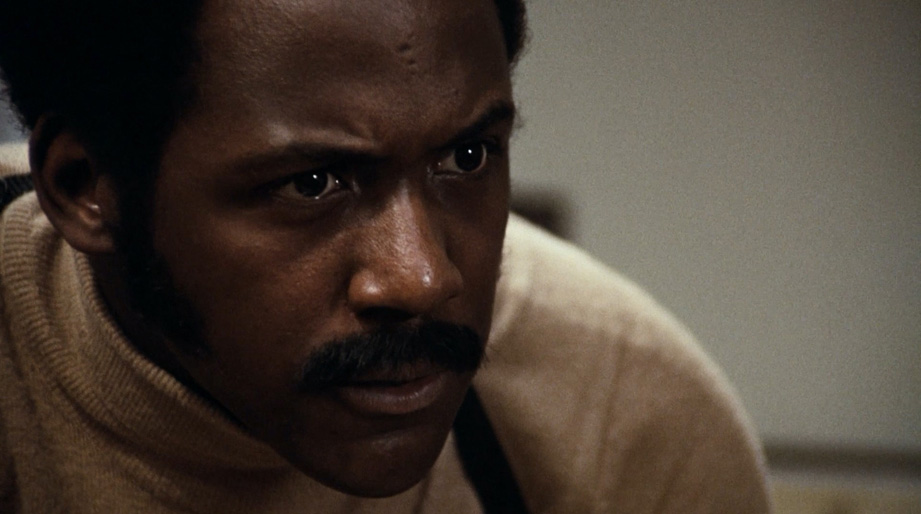

If Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song kicked off the Blaxploitation movement, SHAFT catapulted it into the stratosphere. Released just a few months after Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, Shaft, directed by American photographer, musician, writer and filmmaker Gordon Parks, was one of the first films released by a major American studio to have a Black action hero at the center of its story. The film stars Richard Roundtree as John Shaft, a suave detective who first finds himself up against the leader of the Black crime mob, Bumpy (Moses Gunn), then against the Black nationals, before joining forces with both against the white mafia, who attempt to blackmail Bumpy by kidnapping his daughter. Gwenn Mitchess, Christopher St. John, Charles Cioffi and Margaret Warncke also star. Shaft won an Academy Award for Best Original Song (making Isaac Hayes the first Black man to win an Oscar), grossed over $12 million from its $500,000 budget (saving MGM from bankruptcy), and in 2000 was inducted in the US National Film Registry by the Library of Congress. The film led to two remakes and two sequels, as well as a television series.

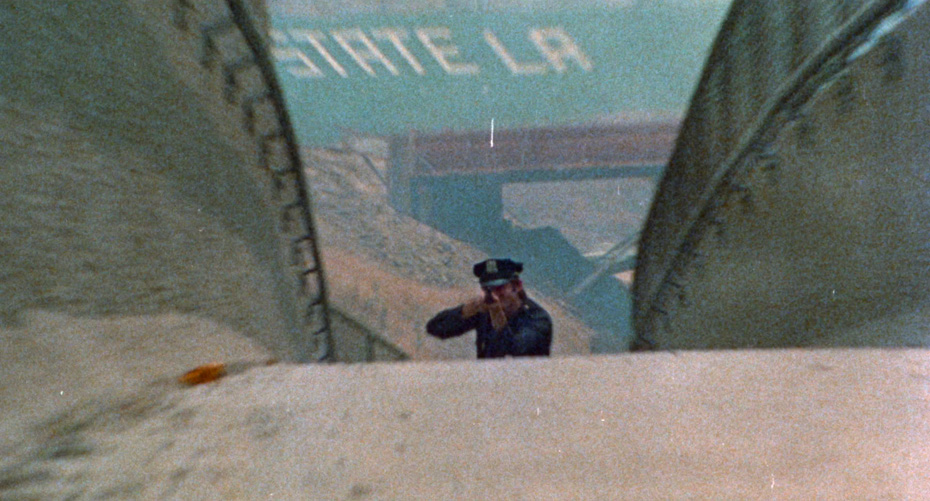

Parks took the influences of his own background as a photojournalist and sought to apply them to the making of Shaft, working closely with Swiss cinematographer Urs Furrer to portray a side of New York that audiences had rarely seen represented on screen. Parks wanted Shaft to showcase Black America in everything from language to style, and brought this radicalism to the film’s visual language as well. One of the key visual characteristics of the film is the way it appears to worship its central character. Parks and Furrer almost always framed Shaft in low-angle shots, and his camera movement was always motivated by Shaft’s. In doing so, they created a relationship between the hero and audience that up until then had been reserved for white characters in American cinema – one in which, in Parks’s own words, would for essentially the first time in American cinema allow audiences “to see the Black guy winning”.

Blaxploitation films didn’t just glorify the Black male hero. By the time that FOXY BROWN was released in 1974, Pam Grier was already the pre-eminent female star of the movement, thanks to 1973’s Coffy. The sequel, Foxy Brown, written and directed by Jack Hill, was her most iconic role, and follows the title character as she poses as a sex worker to take on a gang of white drug dealers who murdered her boyfriend (Terry Carter), an undercover cop. Foxy Brown also stars Kathryn Loder, Antonio Fargas, and Juanita Brown. The film grossed over $2.4 million at the box office from its $500,000 budget, and has since gone on to be considered a cult classic of the movement.

Brown’s resilience, violence and sexuality made her an instant classic amongst Blaxploitation characters. The character was also controversial for the ways in which some audiences saw her as entrenching an attitude of objectification of Black women. Over time, the character has ascended to become a pop culture icon, and an archetypal figure of the 70s nostalgia movement. Both the cinematography and costume design were central to ensuring Foxy Brown’s icon status in the Blaxploitation canon. Hill collaborated with American cinematographer Brick Marquard, best known at the time for his work with Peter Bogdanovich, and with American Costume Designer Ruthie West, who was the stylist for the Jackson 5, Thelma Houston, Bobby Gentry and the Curtis Brothers. Hill, Marquard and West not only ensured that Grier’s character would hold the dominant position in the composition of every frame she occupied, but also that her character’s costuming would create bold and vibrant frames that made Foxy Brown one of the most memorable films of its era.

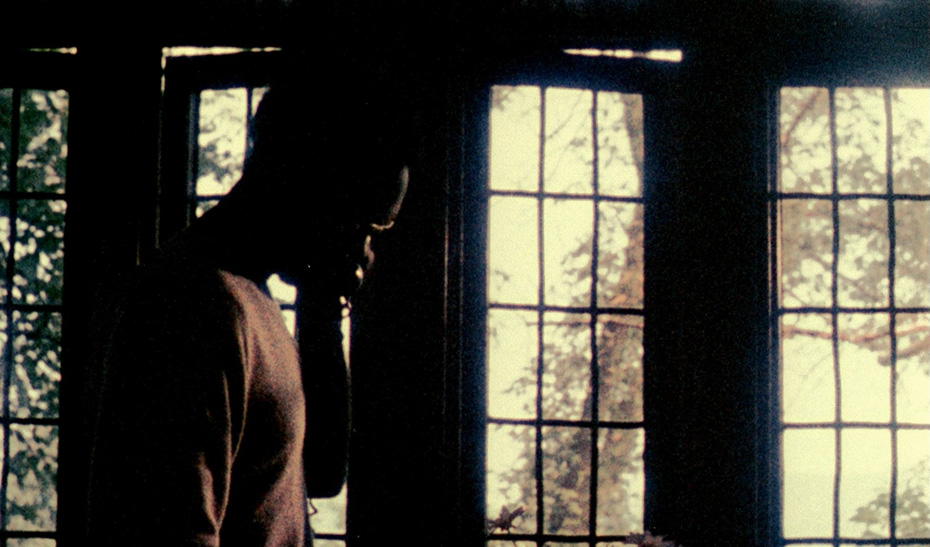

Blaxploitation may be best remembered for its entries in the action and revenge thriller genres, but its footprint extended across many genres, including comedies, westerns, and horror films. Its most notable entry in the horror genre is the 1973 film GANJA & HESS, written and directed by Bill Gunn. The film follows an anthropologist, Dr. Hess Green (Duane Jones), who turns into a vampire after his assistant (Gunn) stabs him with an ancient cursed dagger. Green falls in love with his assistant’s widow, Ganja (Marlene Clark), who eventually learns about his secret. Ganja & Hess was made for $350,000 and premiered at the 1973 Cannes Film Festival, making it the first Blaxploitation film to play at a major international film festival. Today, the film is celebrated as one of the most influential horror films of the 70s, and a singular entry in the movement that many consider to still be ahead of its time. Gunn worked on Ganja & Hess with American cinematographer James E. Hinton, who is widely acknowledged as the first Black cinematographer to have shot a theatrically released American film.

Gunn and Hinton wanted to use the tropes of Blaxploitation cinema as a means of subverting the audience’s expectations for the film. The pair wanted to push the formal bounds of the film through its cinematography and editing. Many of Hinton’s techniques – changes in focus, graininess, under- and overexposure, lack of traditional clarity in the image, and playing with the emulsion – are termed as “haptic visuality” – imagery designed to help evoke other senses as a way of accessing more than what the literal image can provide. This set of techniques ties into the narrative of Ganja & Hess, where Dr. Hess starts to “remember” places through his anthropological research, as well as in the lovemaking scenes, which often doubled as murder scenes.

BLAXPLOITATION’S LEGACY

Blaxploitation films continued to be controversial even as their popularity grew through the 1970’s. By the later stages of the decade, the combination of their divisiveness and the influx of movies made in that mold caused the movement to run out of steam with audiences. The NAACP joined the National Urban League and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to form the Coalition Against Blaxploitation, and by the end of the decade, Blaxploitation movies were no longer a major force in moviegoing culture. But their legacy was well and truly cemented. Blaxploitation remains one of the most enduring movements in American cinema, and its aesthetic influence can still be felt in new movies today.

Black filmmakers independently making important movies was by no means a new phenomenon in the 1970s. But the Blaxploitation movement did give new energy to Black filmmakers in America, and their work influenced generations of filmmakers to come. The low budget independent ethos of Blaxploitation filmmakers was carried through the mid-80s and early-90s by filmmakers such as John Singleton and Spike Lee, who’s early films were made for low budgets and reached international audiences. Singleton would later remake Shaft in 2000, starring Samuel L. Jackson, and Lee would go on to remake Ganja & Hess in 2014’s Da Sweet Blood of Jesus. The use of unconventional camera angles, bold color and lighting design and percussive editorial language tied explicitly to score became trademarks of Lee and Singleton’s work more broadly, as well as of many Black filmmakers in the 80s, 90s and 2000s.

The aesthetics of Blaxploitation movies, in everything from poster design, to songs and movie soundtracks, to characters themselves, have also influenced artists around the world across all mediums. Blacksploitation movies like Shaft have been remade and sequel-ized several times, as recently as in 2019 by director Tim Story, with Roundtree reprising his iconic role. Blaxploitation movies have been referenced and parodied in James Bond films and Austin Powers films, as well as in television shows such as The Simpsons and Family Guy. Blaxploitation movies have been referenced, copied and remixed by white filmmakers such as Quentin Tarantino. Blaxploitation movies have even influenced the world of opera, with directors like Peter Sellars staging Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni in contemporary Spanish Harlem in the manner of a Blaxploitation film.

What started as a low-budget subgenre for grindhouse theaters is today one of the most important cultural landmarks in American history. Its influence can be felt across film, music, art, advocacy and politics. Blaxploitation redefined cool, redefined rebellion, and gave the world a look at Blackness that had never been seen before.