06.13.23

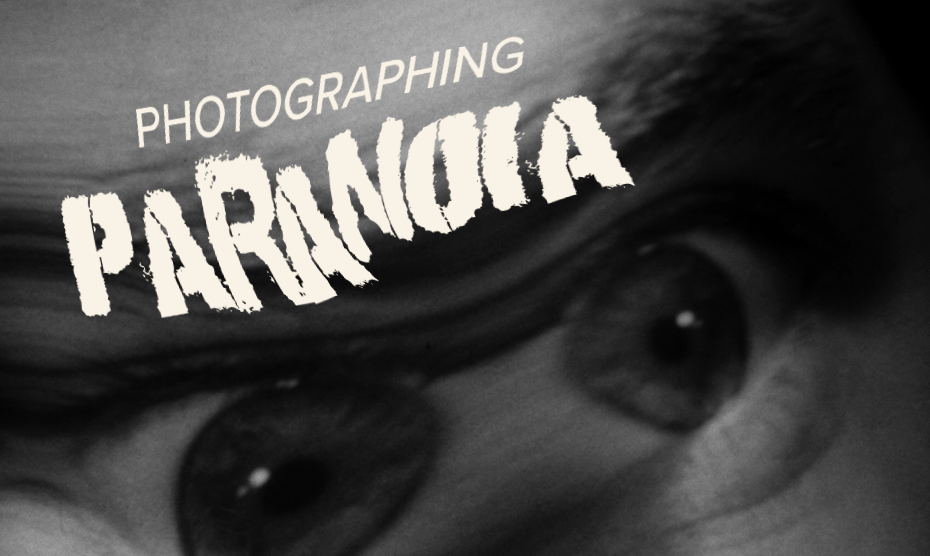

PHOTOGRAPHING PARANOIA: JAMES WONG HOWE’S CINEMATOGRAPHY IN SECONDS

James Wong Howe (born Wong Tung Jim) was a Chinese-American cinematographer who shot over 130 feature films over the course of his career. He was one of the most highly sought-after cinematographers of his era, and one of the most groundbreaking and influential cinematographers in cinema history.

Wong Howe was a pioneer for cinematographers in technique and storytelling as well as representation. For example, he developed the use of black velvet to make blue eyes show up better on orthochromatic film stock (known for causing blue eyes to appear washed out or even totally white). By mounting a frame covered in black velvet around the camera, Wong Howe ensured the reflections would darken the eyes enough to appear more natural in the developed film.

Wong Howe earned the nickname “Low-Key Howe” over his career for his dramatic lighting and use of deep shadows, which came to be associated with American film noirs. He also became known for his bold use of unusual lenses, film stocks and shooting techniques, for creating an early version of the crab dolly, and for filming boxing scenes from Body and Soul hand held while on roller-skates. He also pioneered an early version of the helicopter shot (operated by then-second-unit DP Haskell Wexler), and is credited as one of the first DPs to employ the deep focus technique on the 1931 film Transatlantic, ten years before Gregg Toland used it on Citizen Kane.

Wong Howe was the first person of color admitted to the ASC, and a mentor for other cinematographers of color throughout his career. In spite of the prejudice and persecution he faced in the industry and in the public, he became one of the American film industry’s preeminent artists, and a source of inspiration for filmmakers all over the world today.

There are dozens of films from Wong Howe’s filmography worth studying for their innovations in shooting style, lensing and lighting, from Hud to Sweet Smell of Success to Bell, Book and Candle, and many others. In this post, we are going to focus on a film that, while perhaps less well-known, is one of the best examples of how Wong Howe’s innovative cinematography captured an atmosphere of unease and paranoia – Seconds.

SECONDS (1966)

By the time James Wong Howe shot SECONDS, he had already lensed over 75 feature films. Seconds, directed by John Frankenheimer and written by Lewis John Carlino, is a psychological thriller starring Rock Hudson. The film follows Arthur Hamilton (John Randolph), an unhappy middle-aged banker who agrees to a procedure that will allow him to fake his death and assume a completely new body and identity as Tony Wilson (Hudson), living out his “dream life” in Malibu, unaware of the consequences he’s about to face.

Seconds premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in competition for the Palme d’Or. The film was booed in the theater and derided by critics coming out of the festival. Wong Howe was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Black and White cinematography, but the film was largely ignored upon its release, and widely considered a flop.

Seconds has since grown into a cult classic, celebrated by filmmakers from Park Chan-wook and Bong Joon-ho to Keith Gordon and Troy Miller. In 2015, the US Library of Congress added the film to their National Film Registry.

Seconds is in many ways an outlier in Wong Howe’s career. Filled with grotesque, mutating extreme close-ups, the film’s visual style is experimental and ostentatious, but in total lock step with a controversial and subversive film that inspects the male fantasies of a mid-life crisis with razor-sharp intensity. In many ways, the film could still be considered ahead of its time, with no punches pulled in its treatment of the subject both narratively and visually. It remains a landmark achievement in pushing the form to its extremes in order to capture the feeling of paranoia at the story’s heart.

Here are some of the techniques that help made Seconds one of the most noteworthy of James Wong Howe’s filmography:

USE OF FISHEYE LENSES

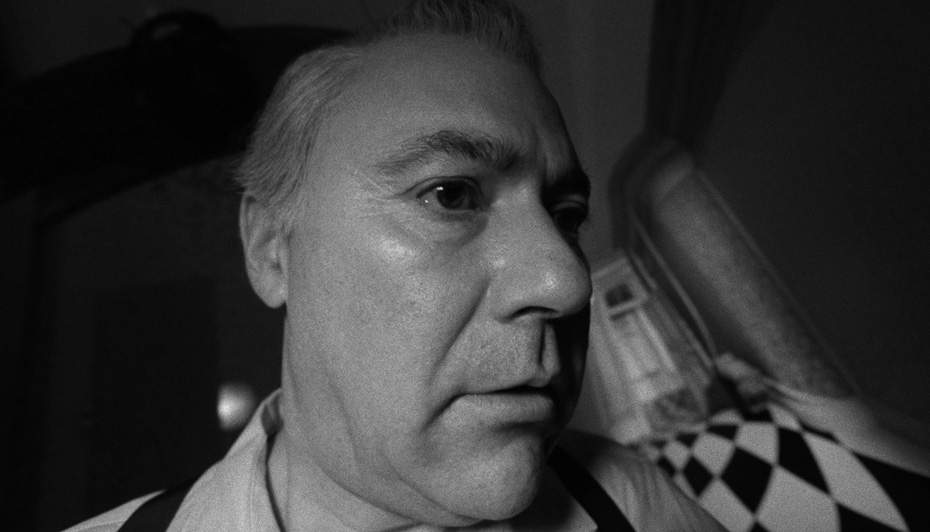

The visual language that Wong Howe and Frankenheimer created for the film was based on being as close to the actors as possible – showing the claustrophobia of Arthur’s life he so desperately wants to escape, and the chaos of Tony’s that he can’t find a way out of.

Frankenheimer wanted to work with Wong Howe, who had a reputation for being strong willed in his vision and a perfectionist on set. He also wanted to push Wong Howe into a more expressionist, experimental visual language to capture the story – an approach that Wong Howe had to warm up to.

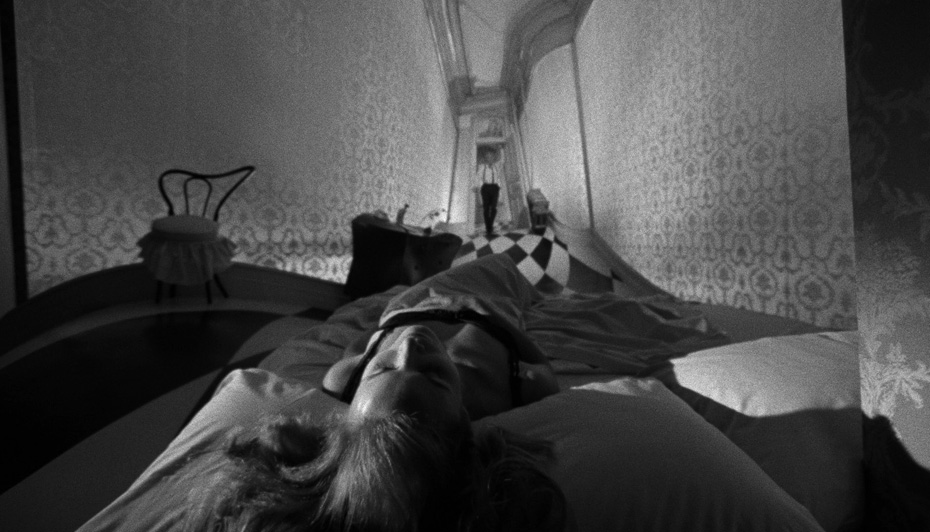

The use of fisheye lenses – often the 18mm or the 9.7mm – ended up being one of the most important visual thumbprints of the film. Used in scenes where Arthur / Tony’s perception of the world and themselves starts to come into question, the fish-eye lens captured a state of paranoia that allowed the audience to feel the same discomfort of the character, pushed into a reality and a way of seeing the world that they were uncomfortable with.

However, the use of fisheye lenses wasn’t initially agreed upon. Wong Howe told Charles Higham, author of Hollywood Cameramen, “On Seconds, I didn’t want the wide-angle lens, the bug-eye. I wanted that journey to the operating theater to be done in a simple style, with subjective camera, but John Frankenheimer differed.”

Wong Howe’s decision to ultimately embrace Frankenheimer’s point of view paid off. Frankenheimer told Gerald Pratley of Variety Magazine in 1969 that “In Seconds, the distortion was terribly important. The distortion of what society had made this man, what the Company then turned him out to be, and finally when he was going to his death everything had to be that complete distortion of reality and the fact that it was all just utter nonsense.”

This attitude was also demonstrated in art director Ted Howarth’s set design. Some of the sets themselves were shot in distorted perspective, such as the chequerboard floor that twists and bends, filmed with a fish-eye lens as Arthur stumbles towards a silently screaming woman.

Because they used such wide-angle lenses so close to the actors, the sound and dialogue often had to be added in post due to camera noise. When asked about whether that was an inconvenience, Frankenheimer told the New York Times: “I believe we are in the movie business, not the sound business. It’s the screen image that is important.”

SHOOTING WITH MULTIPLE HAND-HELD CAMERAS

Wong Howe shot several scenes with up to seven hand-held cameras filming the action throughout takes, creating a frenetic visual energy filled with characters falling in and out of focus, shooting from extreme low and high angles that cut elements of people’s faces off from the frame and feeding into an editing pattern that embraced clashing angles. It was a visual approach that would be considered radical today, and was virtually unheard of in mainstream Hollywood films of the era.

The orgy scene in the grape vat was shot with multiple hand-held cameras, fisheye lenses and peculiarly mounted handheld cameras – all expressing the interior life of Tony in his deranged state, coming into his rebirth in a more desirable man’s body. As Tony loses his sanity, the visual language of the film matches his state of mind, becoming more and more frenetic and unsettling as it races to its conclusion.

Cinematographer John A. Alonzo (Chinatown, Scarface), who got his break working under Wong Howe on Seconds, said “It was a little Arriflex camera and the lenses had those butterfly ears for pulling focus. They had assistants to help you follow focus, but I was a documentary cameraman and wasn’t used to that. Howe said, ‘Can you follow your own focus?’ I told him I could and he basically responded, ‘Well, don’t screw it up kid, or you’re in trouble.’ My first shot had Hudson coming into this crowded living room full of people smoking and drinking. I was in front of him, walking backwards through the crowd, photographing him with a fairly wide 24mm lens. Three cameras were rolling.” Alonzo and other camera operators often physically pulled extras into frame during shots to create more movement and crazed energy during these sequences.

In order to film with so many cameras at the same time, Howe and his team designed an innovative lighting system, which provided “complete lighting of sets for closeups, longshots, etc., sans separate setups, plus the use of ceilinged-sets.”

ATTACHING THE CAMERA TO ACTORS

In the film’s pulsating opening scene, where a man follows Arthur through New York’s Grand Central Station, we watch a camera that feels physically attached to the characters as they move. Wong Howe harnessed a camera with an 18mm lens to actor Frank Campanella, the Company man who shadows Hamilton. This gave the pursuit through the station an off-putting air, keeping him in a locked frame at strange angles as the station swirls around him.

To distract commuters from what was going on during filming, Frankenheimer had a dummy second unit film set up in a separate part of the station. The dummy crew filmed a pin-up girl stripping down to her bikini for an appreciative male actor. Meanwhile, cameras were hidden in a newsstand and the ticketmaster’s office. Several others were few were hidden in suitcases, creating a visual language that accentuated the audience’s sense of surveillance and unease.

Seconds was a movie that Frankenheimer and Wong Howe believed would be lost to time upon its release. But as the film has aged, its boldness of storytelling and stylistic experimentation have helped it stand out as one of the most disruptive and subversive films of its time. Wong Howe, who’s work as a cinematographer on so many of his films is celebrated for its innovation, is at his most experimental in this film, pushing its visual language to places that few studio films have gone before or since. We hope the film and James Wong Howe’s incredible career inspire you to push the possibilities of your next project too!

SOURCES

Cinephilia & Beyond: You Can’t Go Back in John Frankenheimer’s ‘Seconds’

The Oxford History of World Cinema, edited by Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

ASC Magazine: The Surreal Images of ‘Seconds’

NYT: James Wong Howe: A Gutsy Cinematographer Finally Gets His Due

Pop Matters: Sci-Fi ‘Seconds’ Offers a Second Chance at Life: Dare You Take It?