04.11.23

ABBAS KIAROSTAMI, IN HIS OWN WORDS

Few filmmakers have had a more profound influence on world cinema than Iranian writer, director, producer, poet and photographer Abbas Kiarostami. Involved in the production of over 40 narrative features, documentaries and shorts from 1970 to his death in 2016, Kiarostami’s work became synonymous with the Iranian New Wave and with a renewed appreciation for the cinema of the Middle East.

Kiarostami’s films often tell the stories of ordinary people in everyday environments, and embrace a stylistic approach that blurs the lines between fiction and nonfiction filmmaking. Influenced by Persian poetry, they often have an allegorical quality that deals with the political and the philosophical through personal stories, creating what filmmakers like Mike Leigh have termed the “minimalist epic”.

Kiarostami was also a prominent educator, appearing at film festivals and conducting intensive workshops all over the world, including Tehran, London, Marrakech, Potenza, Oslo, New York and Syracuse, to name a few.

Kiarostami’s embrace of fiction and nonfiction filmmaking techniques made him one of the most radical and innovative filmmakers of his era. In this article, we will look at Kiarostami’s thoughts on filmmaking, his sources of inspiration, and the techniques of his craft – all in his own words. In 2015, Paul Cronin edited and published the book Lessons With Kiarostami, a compilation of quotes from Kiarostami over ten years of filmmaking workshops, conversations and interviews. Here are some of the highlights, re-organized alongside the images from some of his most iconic films.

KIAROSTAMI ON FILMMAKING

ON HOW IDEAS COME

Many ideas appear on my doorstep, some more forcefully than others, but most disappear just as quickly. Only the strongest remain, My initial story ideas are sometimes no more than half a page. If I can develop those paragraphs into three pages, I suspect it becomes too detailed – if I can fully visualize the images and hear the dialogue to the point where it feels limiting – then I don’t have much inclination to turn it into a film, so might hand it over to a colleague.

ON MINIMALISM

What is the least amount of information you can give an audience and still ensure that they know what is happening in your film? What can be omitted? What can you remove and still guide your viewers smoothly from beginning to end?

"There is an optimal number of words needed to tell a story. It is almost always the smallest number."

I – and my films – have long since been progressing towards a certain minimalism. I aspire to express myself in the simplest possible language, to strip things down as far as possible and remove superfluous elements. Elements that can be eliminated have been eliminated. Everything redundant is cut away. If the presence of something is of little significance, its absence is preferred.

ON THE IMPORTANCE OF LOCATIONS TO HIS WORK

I don’t write much down before visiting the places where I plan to film. If a scene I am thinking about requires there be a door that someone walks through, I first find a location that contains a real door, then proceed accordingly. Casting that door is just as important as finding the right actors. The filming location, the spaces through which the actors move, are as important as anything else.

ON HIS VISUAL STYLE

When I first started out, I wanted to demonstrate my technical skills as a filmmaker, mainly because people were always telling me I was so lacking in such things. I ended up including fancy hand-held camera movement in my first film. The shots were interesting enough but my attempts at technical virtuosity clearly got in the way of the story.

There must always be a good reason to move the camera. I can’t deny that my camera set-ups are usually quite simple, that I prefer to strip the crew and equipment down to a minimum. In fact, for years cameramen didn’t want to work with me because they considered my filmmaking to be so unsophisticated.

But to focus on anything other than the story is to short-change the audience. If there is anything lasting in your film – if there is poetry – it will reveal itself through the characters, their interactions, and the landscapes they explore together, not a flamboyant camera technique.

"Think about an intricate tracking shot that makes you wonder how the camera got from the courtyard through the window and into the bedroom. You are following the magic of the camera instead of the story."

I never consciously think about the form of my work because form derives from content. Or better, the two permeate each other. You can never separate them. One leads directly to the other. Form is dictated by content.

Consider the differences between 35mm and digital. The choice between the two isn’t predetermined, it depends on the story being told. Once the story is in place, once it is inhabited by characters, the decision about how to represent things on screen – the medium of expression, the form – flows naturally. And if the form of a piece of art is interesting enough, if it is original and innovative, its creator doesn’t even need to think about content.

The content is the form.

"It requires more precision to tell a story in five shots than in twenty."

KIAROSTAMI ON HIS FILMS: WHERE IS THE FRIEND’S HOUSE (1987)

ON THE INSPIRATION FOR THE FILM

Where is the Friend’s House? was inspired by the image of a child running towards a tree at the end of a road that threads its way into a barren hillside. I had been thinking about that one for years. You can see it in my paintings and the photos I was taking at the time. It was as if I were being unconsciously pulled towards this hill with its solitary tree, which I faithfully reconstructed on film.

With Where is the Friend’s House? I rediscovered images of long ago: a street, a dog, a child, an old man, all of which were elements of Bread and Alley, my first film. They came flooding back years later. The dogs that scared me as a child are lurking somewhere in my unconscious. Given the opportunity, those experiences won’t hesitate to burst forth and haunt me.

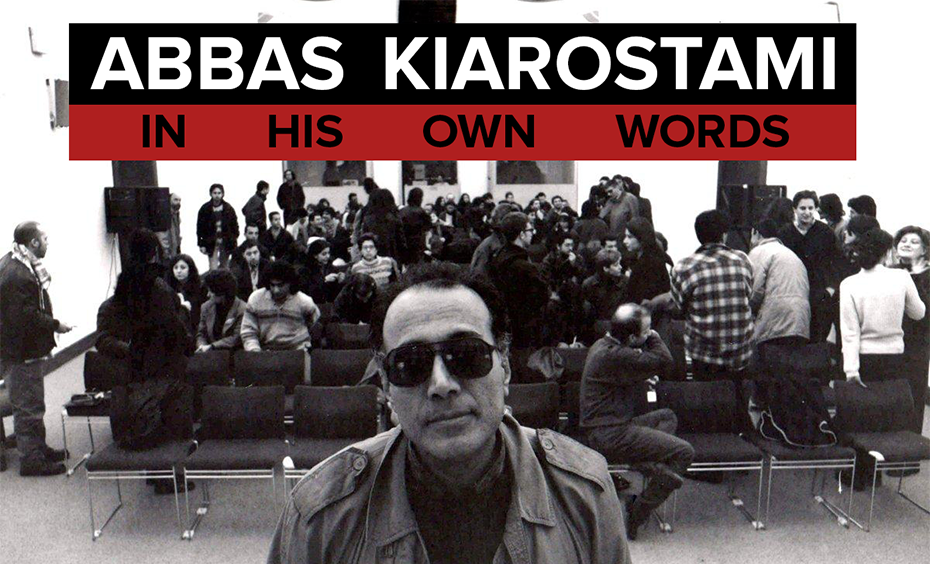

ON FILMING THE CHILDREN IN THE CLASSROOM SCENE

Occasionally, you have to be more mischievous. The children’s faces made it clear they weren’t acting in that scene. Something more serious was going on. I needed Ahmad Ahmadpour, who plays Mohamed, to deliver specific lines while crying, so a week before we shot the scene I asked one of my assistants to take a photo of Ahmad and give it to him. He was excited and loved having this Polaroid. Everyone complimented him on it, telling him how good he looked and how proud he should be of it. I told him to keep hold of it and not let anyone take another photo of him. “Don’t show it to anyone,” I said. “Everyone else will want one too. Behind the boy’s back I asked the photographer to take a second photo of Ahmad and at the same time reassure him, saying that Mr. Kiarostami would never know about it.”

A couple of days later, I went to Ahmad and told him I knew he had allowed himself to be photographed. “Don’t let it happen again,” I said. We did this a second time, which meant there was now a third photograph, which the photographer told Ahmad to hide between the pages of his exercise book. When I confronted the boy and found the third photo, I tore it up in front of him. He began to cry, and with the camera rolling I said, “How many times have I told you not to let anyone else take a photo of you?” Ahmad tearfully responded with “Three times.” I replaced my voice on the soundtrack with the teacher asking, “How many times have I told you to write your homework in your notebook?” The hand you see in the shot is mine, not the teacher’s. He wasn’t even in the room at the time.

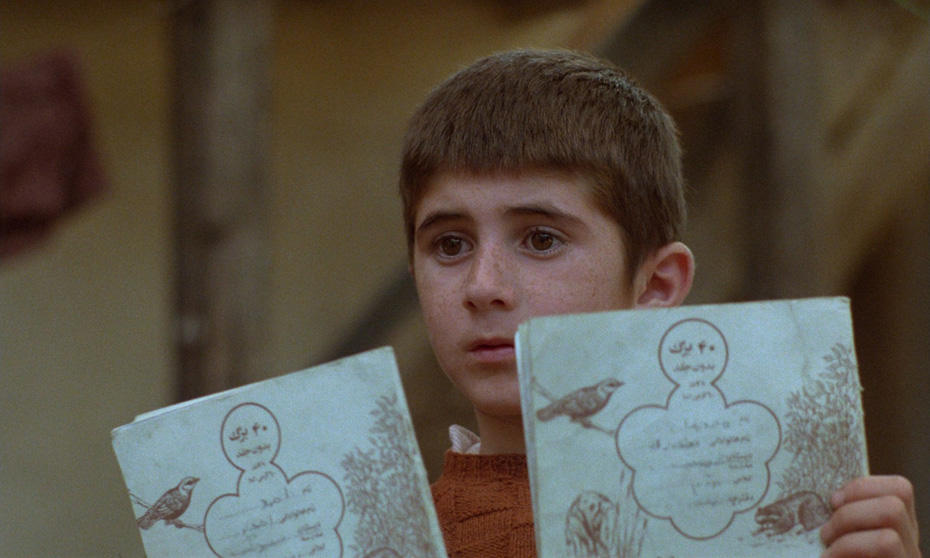

ON THE FILM’S FINAL SHOT

In the last shot of Where is the Friend’s House?, Ahmad’s teacher finds a flower pressed into the notebook, the flower given to Ahmad by the old man the night before. That moment always has a strong impact on audiences, as well as on me when I first thought of it. I wasn’t able to write down anything myself when I first started thinking about the film because I had injured my hand, so I dictated my ideas to a friend, who could never keep up and was always begging me to go slower. I suddenly thought of that last shot of the flower. The image just appeared in my mind. “Quick,” I told my friend, “write this down! Quickly! This is important!” Whenever I see that image, I can’t stop smiling.

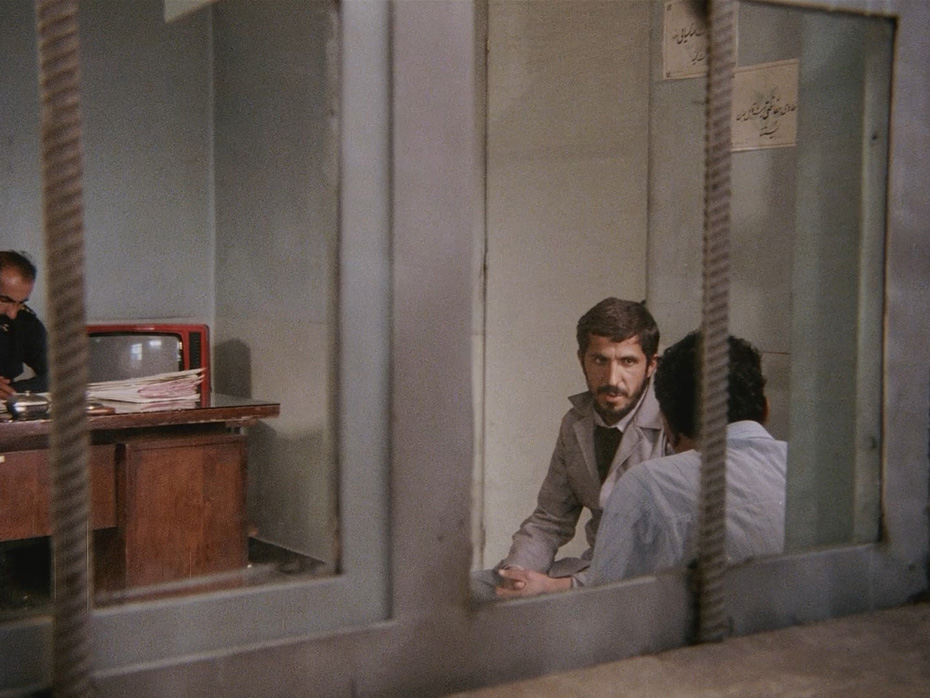

CLOSE-UP (1990)

ON FILMING THE TRIAL SCENE

There is a similar to-and-fro between fantasy and reality in Close-Up. For the trial scene, I planned on having three cameras inside the real-life courtroom. One was for a close-up of the defendant Hossein Sabzian, the second for a wider shot of the courtroom, the third to emphasize the relationship between Sabzian and the judge. Almost immediately, one of the cameras broke and another was so noisy I was forced to turn it off. We ended up having to move our single workable camera from one spot to the next, which meant missing a continuous shot of Sabzian. This is why, when the trial ended after only one hour and the judge left because he was so busy, we filmed with Sabzian, behind closed doors, for another nine hours. I talked with him and suggested what he might say on camera. We ended up recreating most of the trial in the judge’s absence. The occasional shots of him that I inserted into Close-Up, to make it seem as if he had been present the whole time, constitute one of the biggest lies in any of my films.

ON RE-EDITING THE FILM

Mistakes and shortcomings can have a positive effect. The first time I showed Close-Up was in Munich. The projectionist got the reels in the wrong order, though I didn’t say anything because I saw that his accidental version was better than mine. When I got home I re-edited the film and moved the scene of the meeting in the bus – which was originally at the start of the film – to the middle of the trial.

ON THE FILM’S OPENING SHOT

When people hear I won the Palme d’Or at Cannes and see that my films aren’t playing in the local multiplex, and that certain critics like my work, their first thought is that my cinema must be overwhelmingly convoluted. But their expectations are more often overturned and they are genuinely surprised when they come to see that my work is actually quite simple.

The scene in all my films that provokes the most queries is the shot near the start of Close-Up of a can rolling down a street. The number of theories I have heard about that single moment! People don’t believe me when I explain where this image came from. They expect something terribly profound, but the truth is there was a slope in front of the house where we were filming. The important events of the story were taking place inside and I wanted to represent the inactivity of the man standing outside. I created a scene where he would cause an empty spray can to roll gently down the hill. I just liked the image and figured I wouldn’t have many other opportunities to capture a shot like that, one I knew would somehow get audiences involved. We also had time to kill and a few feet of film in the camera. A deadly combination.

ON THE RECEPTION TO THE FILM

I was once introduced to someone with the words, “This is the director of Close-Up,” to which the other person – who wasn’t involved in filmmaking – said, “I didn’t think that film had a director.” What a wonderful concept. An unintended compliment.

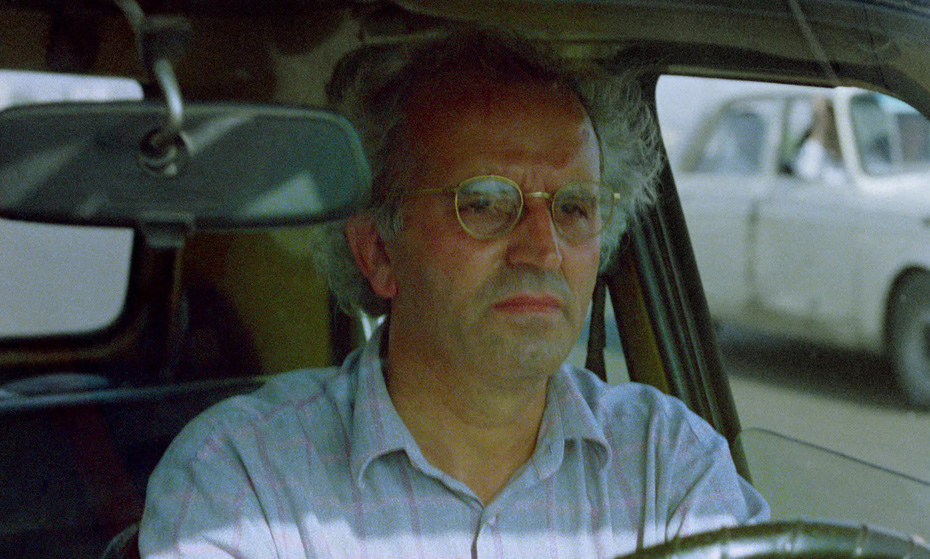

LIFE, AND NOTHING MORE (1992)

ON THE ORIGINS OF THE FILM’S HYBRID FICTION / NON-FICTION STYLE

Life and Nothing More is about a film director returning to an area of Iran where he made a film several years before, and that has recently suffered an earthquake. The film is set three days after the quake but was filmed months later, once much of the debris had been removed and tent cities established. When I asked people who had lived through the catastrophe to put into disarray the few possessions they had salvaged, to make the landscape look more like it had done a few months previously, many refused. Amid the ruin and destruction, they began washing rugs and hanging them on trees to dry, and some borrowed new clothes to wear for the filming. Their instinct for survival was powerful, as was their desire to maintain self-respect in the midst of such harsh circumstances. They wanted to put on a show that didn’t match the reality I was hoping to capture. Like several of my films, Life and Nothing More is simultaneously a documentary and a work of fiction.

THROUGH THE OLIVE TREES (1994)

ON FILMING WITH THE CAMERA AT A DISTANCE FROM THE ACTORS

I planned a lengthy tracking shot for Through the Olive Trees, but the actors were uncomfortable with all those crew members around, so the cameraman put a long-distance lens on the camera and everyone moved fifty meters away. The further away we were, the better the performances became.

In Through the Olive Trees there is an argument between a character in a car and some laborers whose equipment is blocking the way. We experience the incident only through the faces of those involved, and never see the road, yet nonetheless feel we have been shown everything. Our mind is awash with images of that blocked road. Picture a scene in a film where we cut back and forth between two people speaking to each other by telephone. Compare this to a scene where we hear the exact same dialogue, we hear every word being said but see neither of the people talking. We behold something wholly other, something that is, at first glance, completely disconnected from the conversation of these two. Such juxtapositions can be provocative. Why not let the audience do some work?

The cameraman of Through the Olive Trees complained about not being able to see the faces of the two main characters because they were so far from the camera. He wanted to shoot a close-up. I told him it wasn’t necessary, that each member of the audience would do that in their own minds if they wanted to. When presented with intriguing characters in intriguing situations, no matter how far from the camera, perceptive viewers will work things out for themselves.

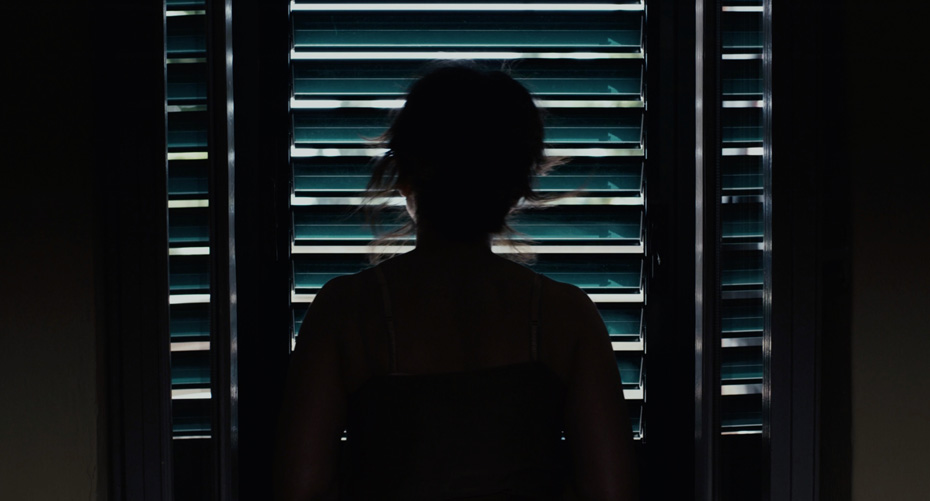

ON THE FILM’S FINAL SHOT

I had something in mind for the final shot of Through the Olive Trees and searched high and low for the right landscape. When I found it, I went back several times to determine what time of day had the most interesting light, which turned out to be just before sundown. The idea was to film from far away so we would see Tahereh in the distance, slowly departing, with Hossein chasing after her. The insurmountable class barrier between them means because her parents – when they were alive – had already rejected him. The dead exert a strong influence in Iran. When someone says something before departing, their decisions are set in stone.

During rehearsals, I watched the two of them walking away, disappearing from view, like two patches of white merging together. We stayed there for twenty days, waiting for the perfect moment, for the most beautiful light, which lasted only four minutes each day. For nearly three weeks I looked at the superb countryside. It was almost like going into a meditative trance, as if the image before me went hand-in-hand with an incantation. Away from the city, codified social differences, the scene takes place within a dreamland that knows no boundaries. As the camera rolled, all real-world problems dropped away. I dipped into reveries myself, hoping Tahereh might at last give Hossein a positive answer. It was a perfect opportunity to break free from the anchor of reality and, for a moment, follow the path of imagination.

TASTE OF CHERRY (1997)

ON CONSTRUCTING THE STORY

The shape of Taste of Cherry is drawn from a Persian poem about a butterfly that flies around a candle, moving closer and closer to the flame until it burns. In the film, Badii drives around in his car until he falls into the grave he has dug for himself.

The story was also inspired by the tale of a man being chased by a lion. To save himself, he is forced to jump off a cliff, but gets caught on the root of a plant growing out of the side of the mountain. He finds himself between the enormous chasm below and the ferocious beast stalking him above. Just then he notices two mice – one white, one black – gnawing at the root he is hanging from. In the midst of this alarming situation, he sees a strawberry growing on the mountainside, and in that precarious situation, fraught with danger and uncertainty, he reaches out, picks the strawberry and eats it.

When we awoke this morning our deaths were further away than they are now. Do all you can to enjoy life.

ON THE FILM’S MINIMALISTIC APPROACH

There is a scene in Taste of Cherry set at the natural history museum in Tehran. Badii looks through the window into a room where students are dissecting quails. We hear them talking with their teacher but see nothing. No scalpel or birds, no teacher or students. All we experience are noises and fragments of dialogue that enable us to visualize what is going on.

Sometimes the sight of someone’s feet is the best indication of his state of mind. Rumi (the 13th-century poet) advises that those who want to see better should open the eyes of their heart.

ON CONSTRUCTING THE FILM OUT OF SINGLE SHOTS

For Taste of Cherry I sat inside the car talking to the person next to me while filming him, which was acting of a sort. I pretended to be someone other than I am because, for those moments, my job was to draw genuine responses from the actors that could be recorded and used in an entirely different context.

The film was made in such a way that Ershadi never actually met any of the people he has in his car. Look again and you’ll see that Badii never appears in the same shot as those three characters. Whenever one of them is on screen, I was on the other side of the camera, responding, eliciting specific reactions and lines of dialogue from him. When you see Ershadi, I was sitting in the passenger seat, operating the camera – which was attached to the door – and talking to him. When you see one of the three men in the passenger seat, I was driving, talking and operating. It was only ever just the actor and me in the car. We weren’t being towed and there was no big crew waiting to jump in as soon as the car stopped. Apart from the sound engineer, who was on the roof, everyone was far away, drinking tea.

I knew it was risky to shoot the entire film from such a small number of angles. But I didn’t want to put the camera on the hood of the car. Almost the entirety of Taste of Cherry is a construct, a series of intercut single shots. Even near the end, when Badii steps out of his car and talks to the taxidermist, we never see them together in the same shot.

I filmed the young laborer first, then looked carefully at the footage, after which I filmed Ershadi, who filled in the gaps, with me in the passenger seat. I did the same with the other two, then pieced everything together. Filming took about six weeks, longer than normal for me because we shot for only two or three hours a day, always in the late afternoon when sunlight was fading. Listen carefully and you will notice very few moments when there is overlapping dialogue. It’s all put together very precisely. Everything you hear is intentional, including street noises and sirens.

I don’t know if I have the audacity to make a film like Taste of Cherry again. The bravery just isn’t in me anymore. I particularly like the series of shots near the end, just before Badii climbs into the grave, of him walking from his car and sitting, overlooking the landscape, smoking a cigarette. It lasts two and a half minutes. Who knows if I have the nerve to do that sort of thing again? Audiences these days seem so impatient.

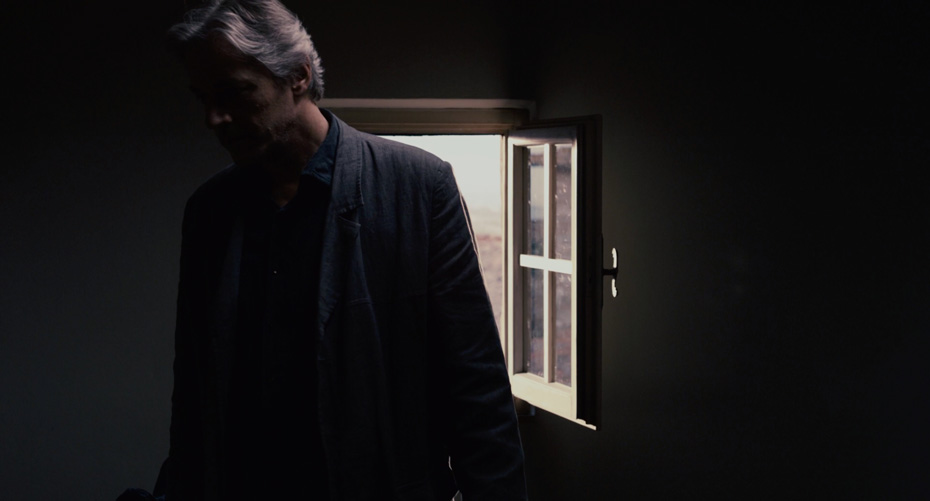

CERTIFIED COPY (2010)

ON THE INSPIRATION FOR THE FILM

Understanding the relationship between storyteller and listener is essential. One of Rumi’s poems tells us that if there is eloquence, enthusiasm and energy within someone, it is drawn out by the listener of the tale. What pushed me to make Certified Copy was the intensity and enthusiasm of Juliette Binoche’s response to the story I told her, the reaction in her eyes, the spontaneous movement of her head. I never had any intention of turning that story into a film, and am sure that had I told it to anyone else I would never have made Certified Copy.

LIKE SOMEONE IN LOVE (2012)

ON THE INSPIRATION FOR THE FILM

The idea for Like Someone in Love was triggered nearly twenty years before I made the film. I was in Tokyo, driving through town late one night, and saw a young girl dressed in a white bridal gown, standing on the pavement, surrounded by businessmen in dark suits carrying briefcases. If I had taken a photograph of this scene perhaps I would never have made the film, but because that photo doesn’t exist I was able to play with the image in my head over the years, steadily adjusting and adapting it, until finally it accommodated other ideas of mine.

KIAROSTAMI ON THE THEMES IN HIS FILMS

I am the last person who should ever talk about the “themes” apparently running through my work. It isn’t my mission to provide statements of intent, and I am unable to answer more questions about what my work means.

My job is to ask questions, not answer them. Besides, I want everyone to have his own interpretation. When Beethoven was asked what he was trying to say with one of his sonatas, he sat down at the piano and played it again. I am like a chef who is so busy preparing a dish he doesn’t even know what it tastes like. The audience’s interpretation is what excites me more than anything, even if it isn’t’ what I am thinking about myself.

Relish the endless ways something can be contemplated. There is no fixed meaning. Ideas about my images and films and poems shouldn’t be given more credence just because I am the one who created them.