THE TUESDAY DROP: 3,800+ New Shots

11.01.22 Get your Decks ready ShotDeck Team! We’re adding the complete first season of Better Call Caul as well as the limited series Small Axe by Steve McQueen, as well as several films honoring the late director Jean-Luc Godard. Check them out below, and remember you can always request films for future drops by clicking here!

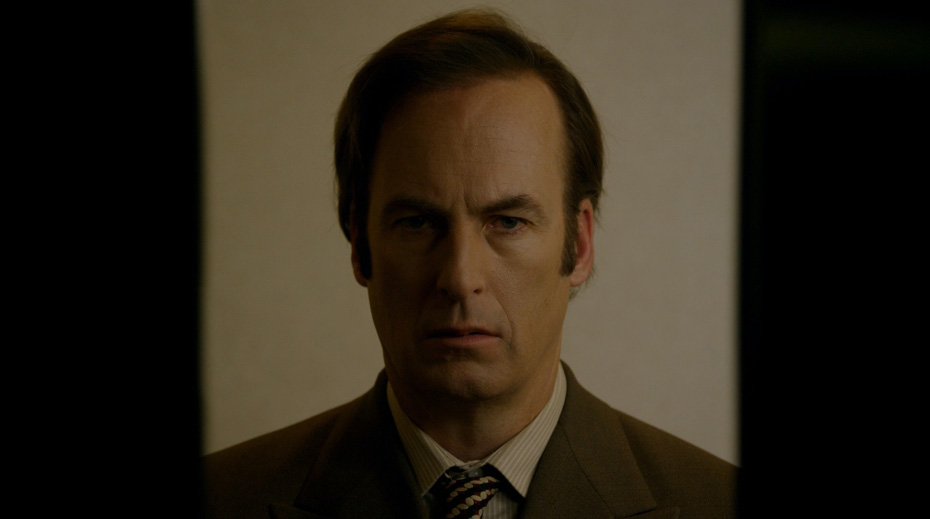

BETTER CALL SAUL: SEASON 1 (2015)

BETTER CALL SAUL is a drama television series created by Vince Gilligan and Peter Gould, starring Bob Odenkirk as James Morgan “Jimmy” McGill / Saul Goodman, a struggling lawyer hustling to make a name for himself and working for often lower-income clients, whose morals and ambitions come into clash with each other. Goodman works with private eye Mike Ehrmantraut (Jonathan Banks), a former Philadelphia policeman turned “fixer”. Better Call Saul is a spin-off of Breaking Bad, which was also created by Gilligan. Season 1 of Better Call Saul appeared on AMC in the United States from February to April of 2015 and was nominated for seven Primetime Emmy Awards. Gilligan and Gould worked on Season 1 with American cinematographer Arthur Albert, who had shot the series finale of Breaking Bad, as well as Happy Gillmore and over 150 episodes of ER.

Gilligan and Gould collaborated with Arthur from the beginning of prep for Better Call Saul that they did not want a complete break from the visual style established in Breaking Bad, but they wanted to push into new territory, and be especially cognizant of doing something different from other television shows, which to their taste had all started to look too similar. The Conformist and the films of Stanley Kubrick became a grounding reference point for all three, leading to relatively unconventional choices such as their first day of shooting being in bright sunlight in a skate park, and the opening of the show being a black-and-white scene of Goodman in Omaha. One major point of departure for the camera language of Better Call Saul as compared to Breaking Bad was that Gilligan and Gould wanted to eschew the handheld look that they had previously established for something far more composed, to the point where they did not want any camera movement at all unless it was motivated by the action in the story.

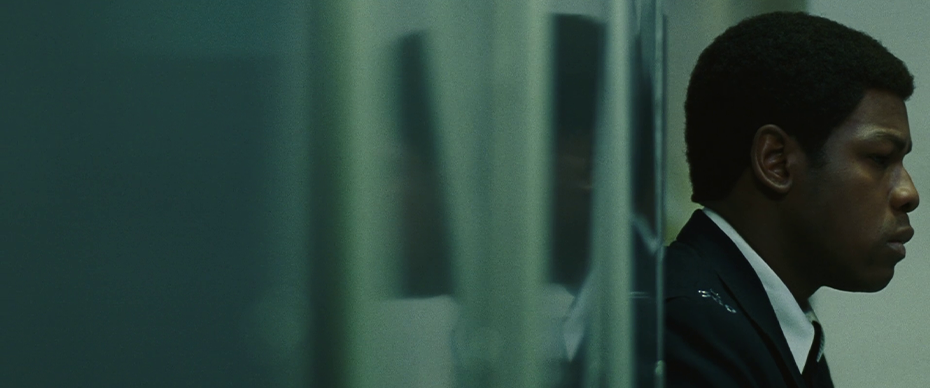

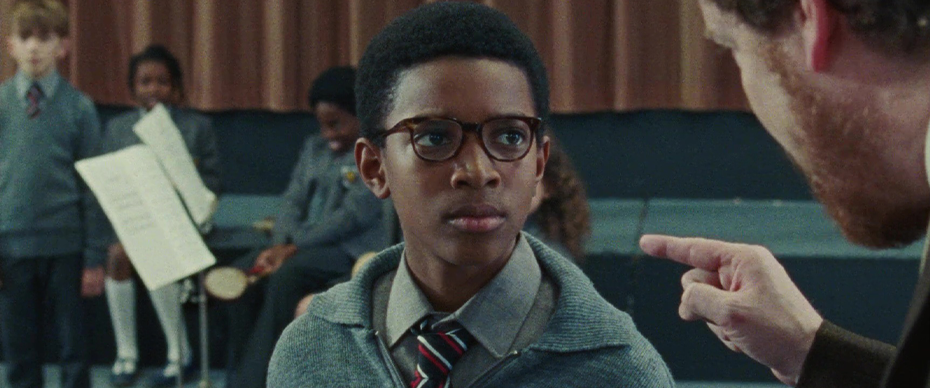

SMALL AXE (SERIES) (2020)

SMALL AXE is a British anthology film series created and directed by Steve McQueen. The anthology consists of five films that tell distinct stories about the lives of immigrants from the West Indian community in London from the 1960s through to the 1980s – Mangrove, Lovers Rock, Red, White and Blue, Alex Wheatle and Education. Lovers Rock premiered at the New York Film Festival, as did Mangrove and Red, White and Blue. Mangrove and Lovers Rock also played at the BFI London Film Festival later in 2020. McQueen worked on Small Axe with Antiguan cinematographer Shabier Kirchner, who up until that point had worked primary as a cinematographer on short films, and had both directed and shot the feature film Augustown.

Kirchner was first approached by Sean Bobbitt (McQueen’s longtime collaborator, who was unavailable to work on Small Axe) after Bobbitt saw Kirchner’s work on the film Skate Kitchen. After being hired, and and McQueen entered their collaboration with the intent to treat each story within Small Axe as a separate, individual film, without the need to force individual stories to have a unified visual language if the story didn’t call for it. Each film’s look and feel was created as a collaboration between McQueen, Kirchner and production designer Helen Scott, with primary importance placed on feeling honest to the period as well to the experiences of the characters within that particular story. Mangrove – a true story centering on the Mangrove Caribbean restaurant in Notting Hill and the 1971 trial of nine people accused of starting a riot during a protest – covered both street demonstrations and a courtroom drama. Kirchner and McQueen chose to shoot on 2-perf 35mm film, because of its ability to capture the feeling of the era, as well as give the story a Kodachrome texture without the intensity of the grain structure that 16mm film would provide. Kirchner shot the courtroom scenes mostly as a series of long takes, working with McQueen and the actors to stage and capture their speeches as they rose to defend themselves. For Lovers Rock – a reference to the Lovers Rock reggae genre – McQueen and Kirchner wanted the film to feel like a fever dream as well as a spiritual representation of the Black love happening on screen, and for the camera to feel like a person at the party. Kirchner shot the film on the Arri Alexa Mini, capturing scenes in a series of long, flowing takes (some carefully choreographed, others shot more spontaneously), with overhead light rigging allowing him to shoot in 360 degrees.

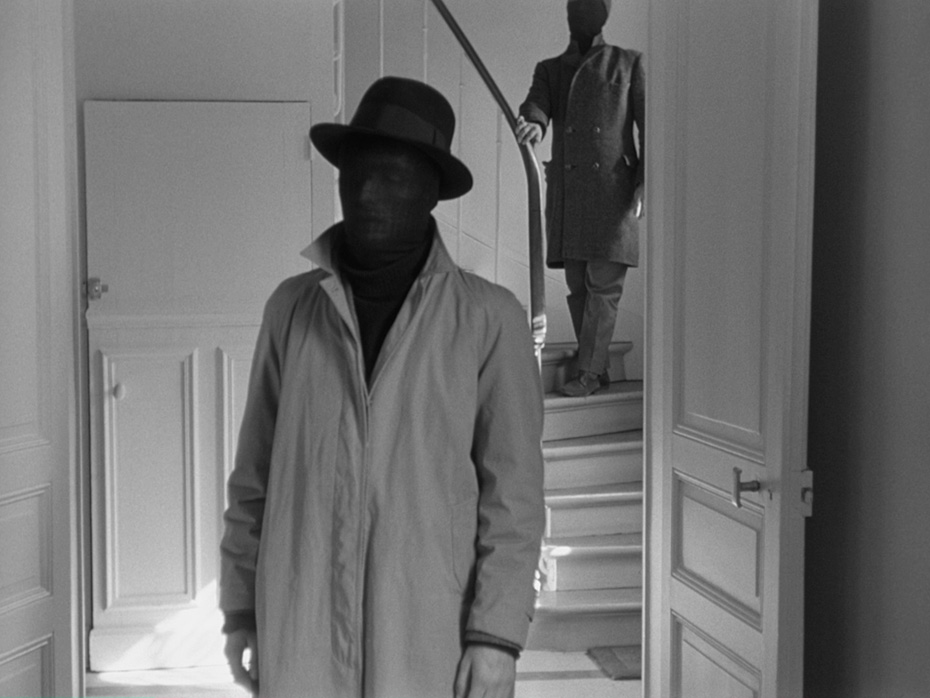

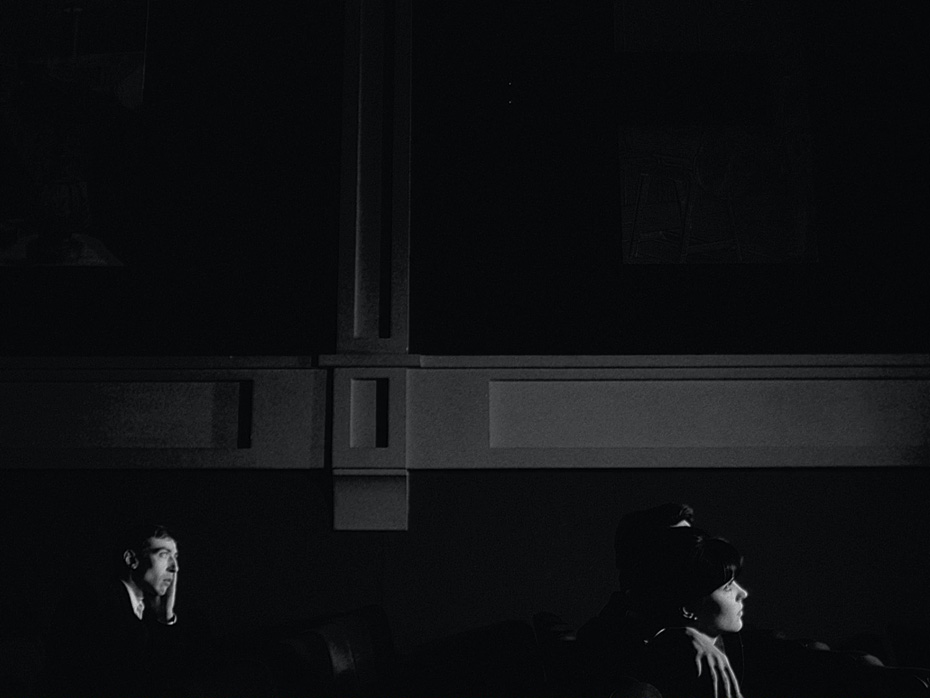

ALPHAVILLE (1965)

ALPHAVILLE is a French New Wave sci-fi noir written and directed by Jean-Luc Godard. The film follows government agent Lemmy Caution (Eddie Constantine), who is dispatched on a secret mission to Alphaville, a dystopian metropolis in a distant corner of the galaxy. Caution chases down rogue agent Henri Dickson (Akim Tamiroff) and a scientist named Von Braun, the creator of Alpha 60, a computer that uses mind control to rule over residents of Alphaville. He is aided in his mission by Von Braun’s own daughter, Natacha (Anna Karina). Alphaville won the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival, and has become one of the most culturally significant sci-fi and noir films of the 1960s. Godard worked on the film with French production designer Pierre Guffroy. Guffroy was known for his work on films such as Is Paris Burning?, Tess, The Tenant and Pierrot le Fou.

Godard and Guffroy wanted Alphaville to serve as a critique of the Modernist age they were experiencing, and took the decision that unlike the set- and production-heavy aesthetic of most major sci-fi films, Alphaville would be shot on location in Paris, using the mega-scaled Modernist high-rises on the city’s outskirts as the backdrop for the anonymous metropolis in which the story takes place. Guffroy’s production design work was enmeshed with his and the location team’s scouting work, with spaces designed to feel ultra-slick, uniform, and ultimately forgettable. Coupled with Raoul Cotard’s cinematography, Alphaville created an ultra-slick film noir look and feel for a world that ultimately alienates its characters.

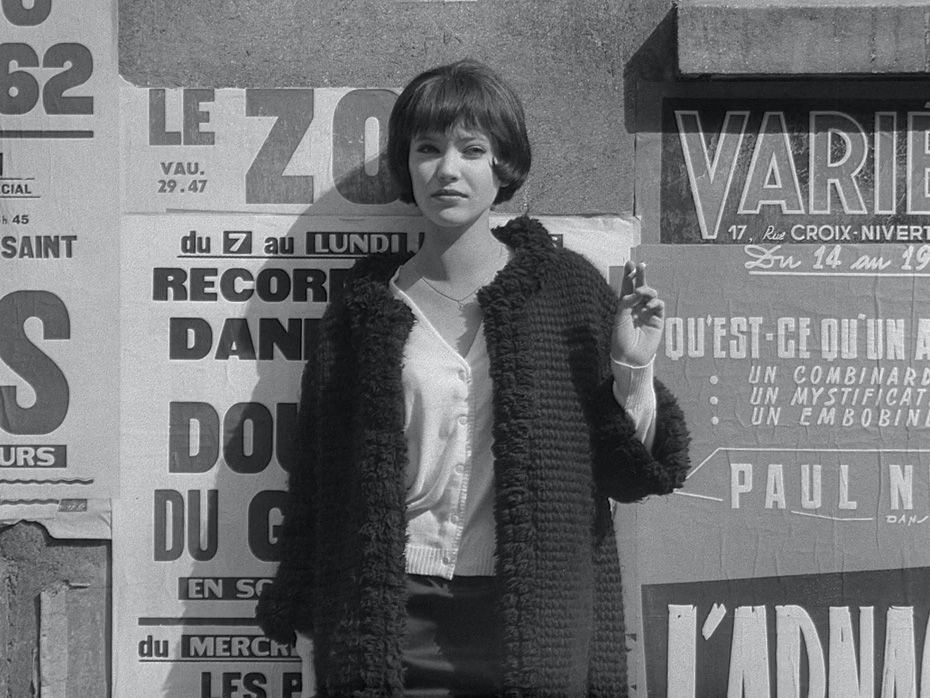

BAND OF OUTSIDERS (1964)

Jean-Luc Godard’s 1964 French crime drama BAND OF OUTSIDERS tells the story of two cinephiles, Franz (Sami Frey) and Arthur (Claude Brasseur) who spend their days mimicking their favorite antiheroes of Hollywood noirs and westerns, while competing for the attention of a young woman, Odile (Anna Karina). When the trio team up to plan their own heist, their romantic visions of a life of crime suddenly start to sour. Band of Outsiders became a quick hit with critics upon its release, and a landmark film in Godard’s career, with several scenes, such as the famous dance sequence and the Louvre running scene, becoming iconic moments in film history. Godard worked on the film with regular collaborator Raoul Coutard, with whom he also shot films such as Breathless, Contempt, Vivre Sa Vie, Weekend and Alphaville.

Godard and Coutard wanted to create a radically different visual language to the one they were used to, relying on Coutard’s background as a war photographer to film handheld shots with minimal film lighting that, in combination with Godard’s working style of writing scenes day by day and sometimes in the moment, created a reportage style of photography for Band of Outsiders. Coutard shot the film with a lightweight Arriflex camera, as well as with a Mitchell camera as the alternate. To be able to shoot sync sound, Coutard built a small blimp around the Arriflex to muffle its sound. For indoor scenes, Coutard and Godard invented a three-wheeled dolly that they placed the Mitchell camera on. This dolly system became known and used widely as the western dolly. Coutard had minimal, often amateur lighting gear, and since many of the shots were filmed in 360 degrees, Coutard and his gaffing team would rig lights to the ceiling along with reflectors to avoid seeing boom or camera shadows in the scene.

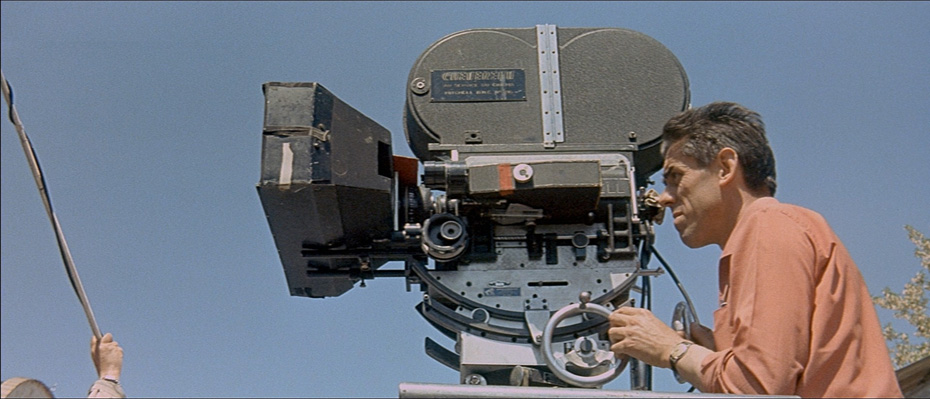

CONTEMPT (1963)

CONTEMPT is a 1963 drama written and directed by Jean-Luc Godard, based on the 1954 Italian novel Il disprezzo by Alberto Moravio. The film stars Michel Piccoli as Paul, a screenwriter hired by producer Jeremy Prokosch (Jack Palance) to energize a script adaptation of The Odyssey when it seems that the hired director, Fritz Lang (played by Lang himself) is turning the film into a box office bomb. Professional and personal clash when Paul falls into an argument with his wife Camille (Brigitte Bardot). Godard worked on the film with French cinematographer and longtime collaborator Raoul Cotard.

Contempt was filmed in Italy, primarily at the Cinecittá film studios in Rome, as well as the Casa Malaparte on the island of Capri. Godard and Coutard wanted to create a visual language that would work within Godard’s style of working with his actors, one which relied a lot upon asking them to improvise dialogue and create scenes in the moment, rather than pre-conceiving scenes too closely in the script phase. Coutard would often film scenes as an extended series of tracking shots, largely using natural light and shooting in real-time, creating a visual language where scenes would evolve within shots, as opposed to being more reliant on editing.

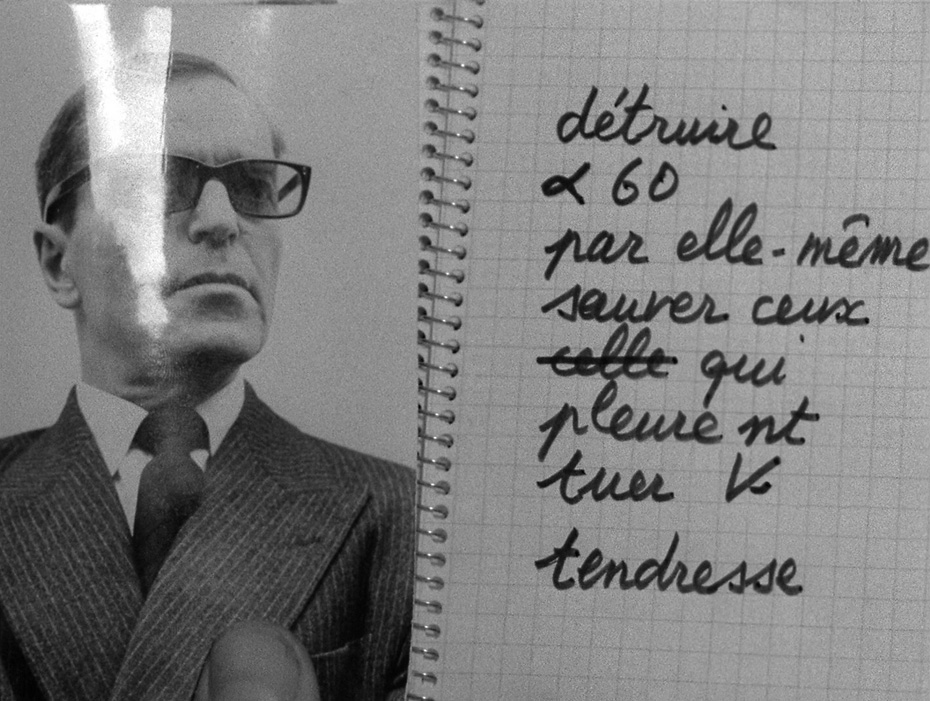

VIVRE SA VIE (1962)

Jean-Luc Godard’s 1962 drama VIVRE SA VIE follows Nana (Anna Karina), a young Parisian woman who works in a record shop and finds herself disillusioned by her collapsing marriage and financial state. Nana tries to break into the film industry as an actor, but turns to sex work, and finds herself between a man who cares for her (Peter Kassovitz) and her pimp, Raoul (Sady Rebbot). Vivre Sa Vie was shot over the course of four weeks for a budget of $40,000, and premiered at the Venice International Film Festival, where it was awarded the Grand Jury Prize.

Godard worked on the film with longtime collaborator Raoul Coutard, who also worked on films with Godard such as Weekend, Contempt and Alphaville. Vivre Sa Vie is told through a series of 12 “episodes”, each of which is preceded by a written intertitle that explains what is to come in that chapter of the film. Godard was influenced by the “epic theater” of German filmmaker Bertolt Brecht, pushing a bold cinematic style that involved unusual camera and editorial choices. Coutard and Godard borrowed from the aesthetics of the cinéma vérité approach to documentary filmmaking which was becoming popular among other films of the French New Wave at the time, but decided to push into slightly different territory by filming with the heavier Mitchell camera, as opposed to the lightweight cameras being used on other productions, which in turn had an effect on the composition style and framing of Vivre Sa Vie.

WEEKEND (1967)

WEEKEND is a 1967 French postmodern dark comedy written and directed by Jean-Luc Godard, starring Mireille Darc and Jean Yanne as Roland and Corinne, a couple on their way to a weekend getaway in the French countryside to collect an inheritance from a dying relative. Both are thinking about cheating on the other, but everything devolves into chaos when they end up ensnared in a traffic jam along the way. Jean-Pierre Kalfon and Saint-Just also star. Godard famously ended Weekend with the declarations “End of Story” and “End of Cinema”, and the film is seen by many as an ending point of Godard’s relationship with mainstream commercial cinema, and a marker of his transition into what could be called the “late” style of his career, marked also by films such as Adieu au langage (Goodbye to Language). Godard worked on Weekend with French cinematographer Raoul Cotard, in what would be their last collaboration for over a decade.

The cinematography of Weekend was marked most famously by its famous traffic jam sequence – one of the longest traveling shots in cinema history, where Coutard placed a Mitchell camera on a 300 meter-long dolly track to view a traffic jam, where all the cars except Roland and Corinne’s remain trapped as they serenely drive past them, until we arrive to a harrowing roadside car crash with bodies strewn across the road. Godard self-sabotaged the opportunity to showcase the technical mastery of accomplishing this shot by interrupting the shot with repeated intertitles, ruining the continuity of the shot and highlighting the nihilistic attitude of the filmmaker to commercial cinema in general through this film.